by Patrick Ropp—GBI Technical Advisor

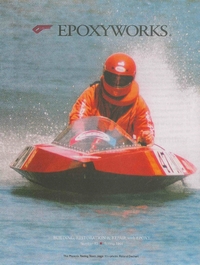

Tiptoeing on the edge of danger, I was crouched down on my knees in the cockpit of my ten-and-a-half foot “sheet of plywood” hydroplane, screaming across the water at speeds reaching 65 mph. Crossing the start line with wide open throttle, I, along with eleven other boats, aimed for the first turn pin. Who will make it there first? With just inches between boats, whitewater from the roostertails engulfed my boat and hammered against my helmet’s visor. These roostertails, which extended thirty feet behind the engine and turn fin, were difficult, almost impossible, to avoid. During this moment of frenzy, I prayed that another hydroplane had not stalled in front of me, or worse . . . flipped.

At the bottom of the 9,000 RPM engine spun a three bladed propeller, sharp enough to shave with, each blade’s tip turns at speeds of that of the engine. The stakes were high, and a good position out of the first turn could increase the odds of another victory. Quick wits and decision making, a driver’s skill, a well-tuned engine, a tested and trued propeller and a structurally strong boat, would differentiate first from second place. The last thing I needed to worry about is whether my boat would stay intact . . .

After decades of building racing boats, the Phoenix Factory was still producing Phoenix Flame Hulls, primarily hydroplanes and runabouts raced in sanctioned American Power Boat Association’s (APBA) Stock and Modified Outboard divisions, and in sanctioned American Outboard Federation (AOF) races. Ever since we changed adhesives in 1982, WEST SYSTEM® epoxy is the only epoxy used in each boat to bond all parts together and encapsulate the entire boat. Other epoxy systems have been tried, but couldn’t satisfactorily withstand the beating and abuse encountered by a 9′ – 13′ racing boat.

Several years ago my father (Dale Ropp), two brothers (Jeff and Topher), and I started using WEST SYSTEM epoxy to build outboard hydroplanes and runabouts. Six years before using WEST SYSTEM epoxy, we were using Weldwood Plastic Resin Glue as an adhesive and polyester resin/fiberglass as a coating. We discovered that the adhesive wasn’t very good at gap filling, the joints had to be perfect, and we needed high clamping pressure. The polyester coating didn’t like to bond too well to the wood. It was temperamental, and worked only 30 percent of the time. After taking advice from a local boat builder, we switched to epoxy for both adhesive and coating. We started off with the best on the market, Gougeon Brother’s WEST SYSTEM epoxy. My father made a trip to Bay City to find out more about this strong adhesive and tough coating. Some of my dad’s customers asked specifically for WEST SYSTEM, and were happy to find out he’d been using it on their boat.

From humble beginnings

We accidentally stumbled into the race circuit while driving around the countryside during a family weekend outing near our new home in Marysville, Michigan. As it turned out, there was only one more race left in the season. Our racing team started very humbly. We took a small, home-built 8′ runabout, (originally a Popular Mechanics plan made for “puddle jumping”), and a pieced-together engine to a pond for the last race. We ended up receiving a third place overall for the entire season! The racing bug bit hard and it hasn’t yet let go.

The next season we bought a “real” 8′, three-point hydroplane, Lil Miss, and were then able to compete in a couple of classes, both hydroplane and runabout with one outboard engine. Eventually, we bought the remains of another three-point hydroplane that had been involved in a crash which left the driver fatally injured. The boat’s port side was completely ripped away, right down the centerline. My dad was able to revive it and the next year we started to win some races with it. Because of the humble beginnings and creating a regular competitor out of a pile of junk, the Ropp Racing Team took on a new name: The Phoenix Racing Team. Just like the mythological bird, out of the ashes (the junk engines and wrecked boat) emerged a racing team that was becoming more and more competitive. We stood out in the pits, our bright red jumpsuits made us easy to spot in a crowd. Over the years and after many trials and errors, we became one of the teams to beat in the racing circuit. By no means did our team single-handedly dominate each class, but if our team was not one of the first three across the finish line, the boats we built for other drivers were.

As the years went by, the racing team grew. Many friends of the family joined the team and helped out, notably the Lundman family and the Sieman family. At the height of our racing career, we hauled a thirty two foot trailer, which carried seven boats and fourteen engines, across the Midwest — racing against the best the country had to offer. Some of the national titles we captured over the years were: six APBA National Championships, ten APBA National or Regional High Point Championships, one Established APBA Formula E Hydro World Record, two APBA C Modified Hydro World Records, one Induction to the 1986 APBA Hall of Champions, and one APBA North American Championship.

The heart of the Phoenix Racing Team and its success is due to my father’s dedication to quality materials and craftsmanship; honesty and respect for others; and the love of carpentry. When we started racing, the entire racing experience had a positive influence on my brothers’ and my life. Designing and building all of our boats and repairing boats and engines in the race pits, taught us how to quickly troubleshoot and solve problems. Moving at high speeds across the water taught us how to think quickly and how to react to adverse situations. Racing with each other, feeling the thrill of victory and, sometimes, the agony of defeat, taught us both teamwork and sportsmanship. These experiences and the knowledge learned from them are not things which come from a text book. Mom always knew where her boys were, if we weren’t studying or practicing for school functions, we were working in the shop, getting ready for the racing season. There just wasn’t much time to get into trouble. The long and short of it was that if we wanted to race, we had to work on the boats and engines.

Building the boats

From start to finish, each boat is carefully designed on paper and transferred to plywood. There are many parts of the boat that could be expedited, but careful attention to detail always prevails. For example, all plywood boat bottoms were arranged with the grain of the outer veneers laid the across the width of the boat, so that there are more plies running transversely and creating a stronger hull. Because they’re placed in this manner, the bottoms must be scarffed every 4′. Allowing the outer plies to run longitudinally would be a much easier task and only one scarf would be needed. But, this construction technique require a minimum of two, many times three scarfs.

The boats are started upside down, like many other boatbuilding techniques. The plywood cockpit sides are attached to a jig. The transverse frames are laid into slots in the cockpit. Each joint is glued together with WEST SYSTEM epoxy. Then the longitudinal stringers are nestled into dados in the frames. By using dados, and nestling the stringers and frames together, the kneeling board is lower — this forces the center of gravity down, increasing stability, and lowering the drag coefficient. After the frames and stringers are in place, the bottom panels are fit, coated with epoxy, and attached. The rest of the chines and bottom skins are also fit, coated with epoxy and attached to the hull. Staple holes are filled and sanded and the bottom of the boat is given a few coats of epoxy to encapsulate the wood. Sometimes carbon fiber or fiberglass is strategically placed to reinforce highly loaded and high-stressed areas, including the aft three feet of the bottom, which takes most of the pounding.

The boat is then flipped right side up and the deck stringers are installed and the decking is fitted, coated with epoxy and attached. The finishing trim is completed and the boat is washed, sanded and finished. Specially designed hardware is used to outfit the boat and prepare it for power. When preparing the boat for finishing, we found that the outer skins could actually be sanded too finely. We used to sand the decks down to 400 or 600 grit wet/dry, but after seven or eight years of service, the finish on the boats would start to peel off, making it necessary to refinish. By using an orbital palm sander and not sanding too fine, we were able to shorten the sanding time and prepare a better surface for a protective coating, which tends to last more seasons.

Looking ahead

Even at age fifty-eight, my father is expecting big things this year in the world of racing. This winter he is building another boat for himself and boats for three other racers, one is a direct competitor. His new engine has all of the bugs worked out and his new propellers are ready for testing. My mother is patient and still waiting for him to actually “retire” from racing (something he’s been saying for the last ten years). One of these days, mom will get her wish, but until then, faster boats have to be built, stronger construction materials need to be tried and tested, and of course, the ratty old jumpsuits need to replaced. Although I’m not currently involved in the racing circuit, I often think about screaming across the water in my hydroplane, whether it was competing for a national championship or for points, the thrill and excitement was always there.