Technical Staff Report

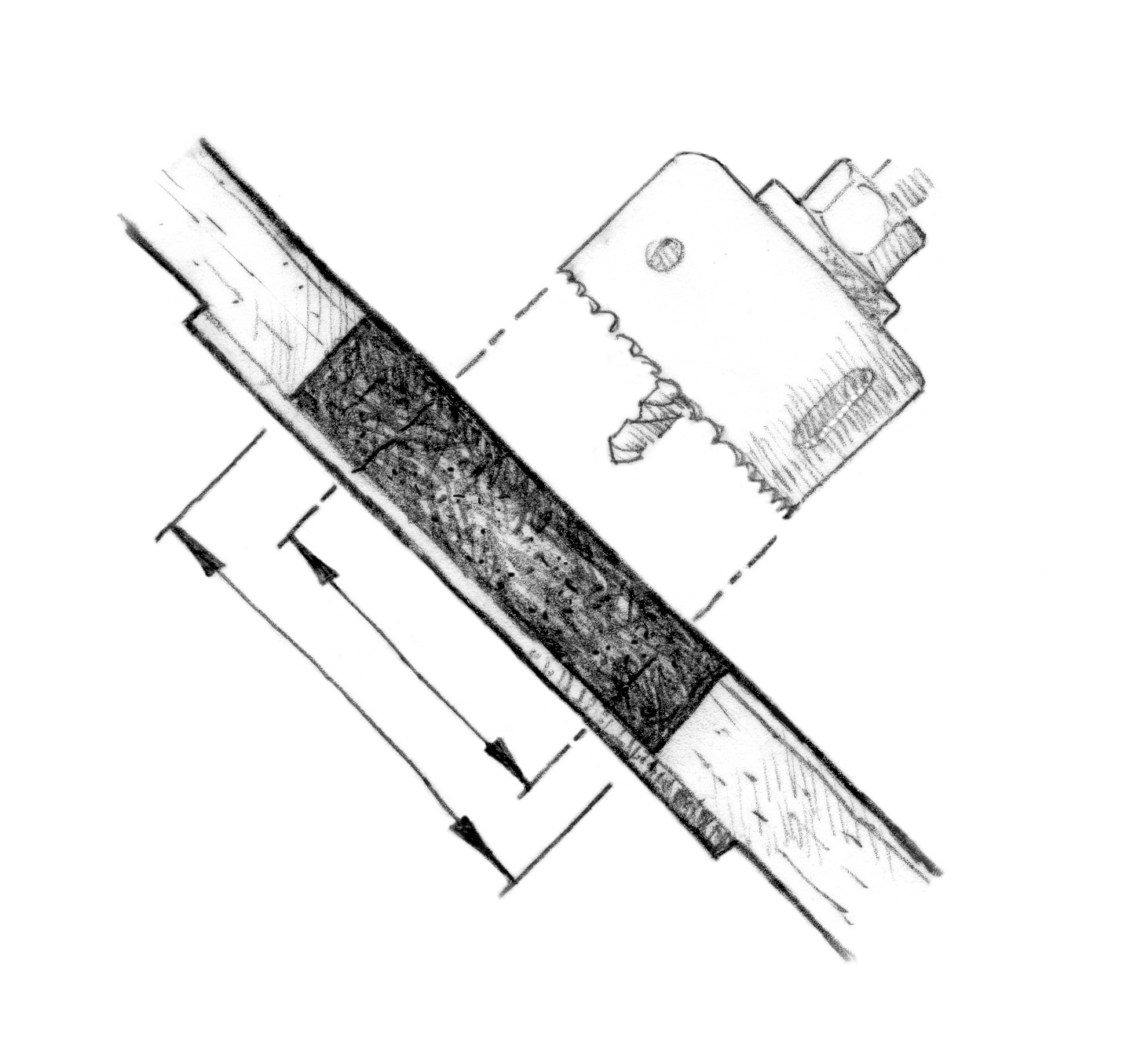

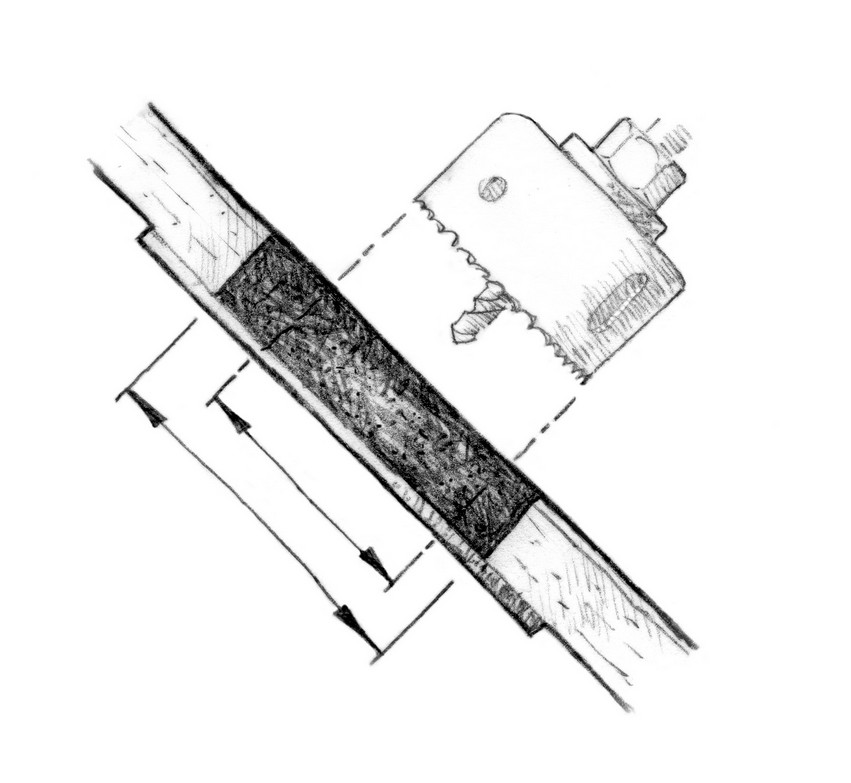

Above: When repairing machined holes in fiberglass, whether screw or a through-hull fitting like the one for the pictured seacock, your strategy will depend on the size, purpose, and location of the hole.

First, we will classify the types of holes we are discussing as ones that are round and have been machined, probably with a drill, as opposed to punctures and cracks incurred from damage. The reasons they may need to be repaired are numerous: refitting, resizing, removing obsolete equipment, or mistakes. When repairing machined holes in fiberglass boats, the challenge is to determine an appropriate repair strategy. You want a repair that is safe and adequate, but also realistic. You want to ensure that the repair is strong enough for the anticipated worst-case load and err on the side of being conservative. Other things to consider include the costs in time and money and the skill required to perform the repair.

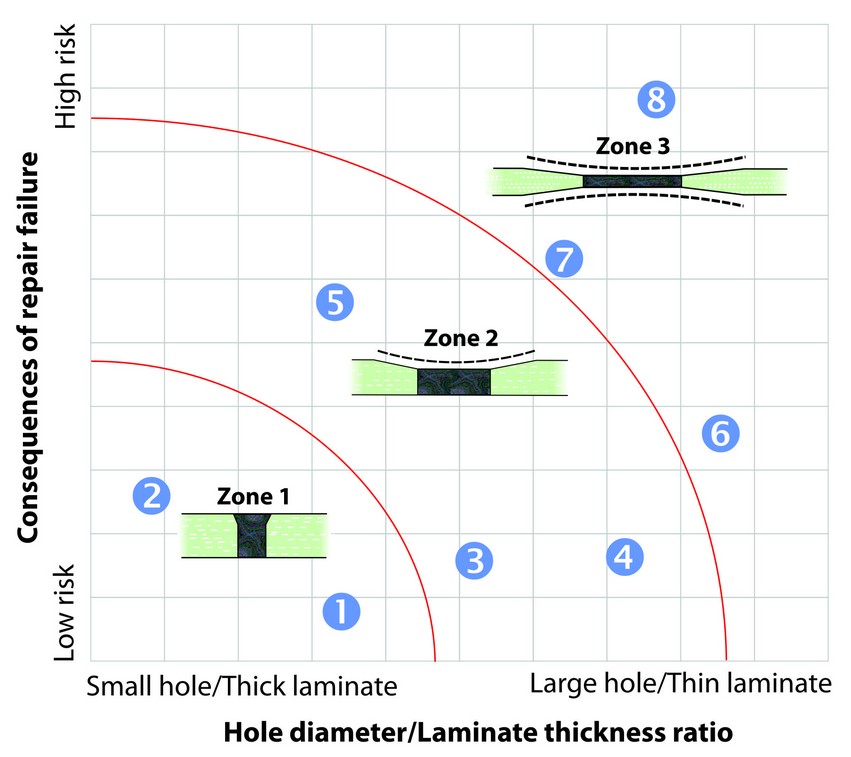

Few repairs are identical, and many variables can influence the appropriate repair strategy. In a best-case scenario, a repair can be very simple: force thickened epoxy to fill the hole, scrape it flush, and allow the epoxy to cure. At the other extreme, a repair of structural fiberglass might involve grinding both sides, bonding in reinforcing fibers, sanding the entire repair flush, gelcoating, and finishing to a high gloss. The first job could take ten minutes and the latter many hours, if not days. There is no tidy repair sequence for repairing machined holes in fiberglass. First, you need to think carefully about each hole. The chart above and this discussion of different types of repair strategies from the simplest to the most complex can help you decide the best repair strategy for most hole repairs.

Use this chart by finding a vertical line on the graph that balances both hole diameter and laminate thickness. Determine the consequences of repair failure and find a horizontal line that represents the level of risk. Where the lines intersect will determine the importance of repair strength. Repairs that are in the upper right corner need to be done very conservatively, and repairs that are in the lower left corner can place a lower emphasis on strength. The chart also demonstrates the relationship between thickness and hole diameter. A hole with a large diameter is more highly stressed in a thin laminate than in a thick laminate.

Keep in mind that in all repairs, regardless of materials or technique, bonding areas must be CLEAN and DRY and either POROUS or SANDED to provide tooth for good adhesion.

Clean surfaces with an appropriate solvent to remove oil, grease, wax, sealants or other contaminants. Use a heat gun or hairdryer or allow bonding surfaces to dry thoroughly. Sand non-porous surfaces with 80-grit paper to provide a texture the epoxy can “key” into.

Zone 1—Low-risk repairs using thickened epoxy

The following two examples can be repaired with thickened epoxy because their characteristics put them in the lower left-hand corner of the chart. They require no additional fiberglass reinforcement.

Example 1

A #8 self-tapping screw (just over 1/8″ in diameter) is removed from the deck of a boat. The deck is 1/8″ thick fiberglass skin with a plywood core.

This is a low-risk repair. The hole is small in diameter, the skin is relatively thick compared to the hole diameter, and the skin is backed by dense core material, plywood. If this repair fails, the worst thing that will happen is the plywood core may rot someday.

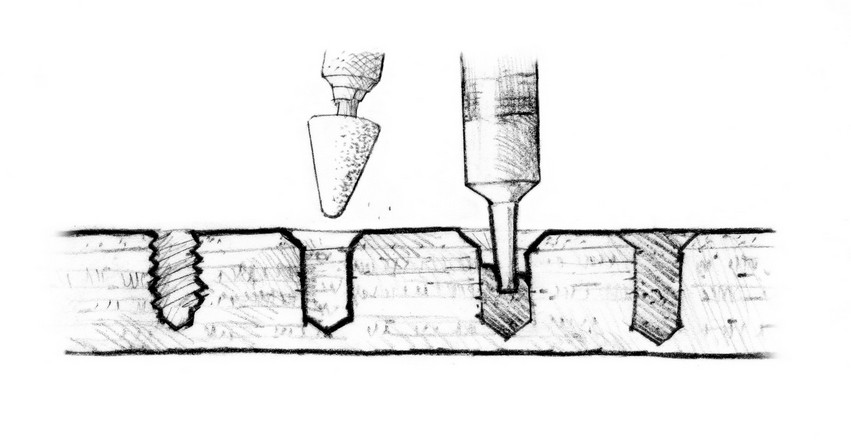

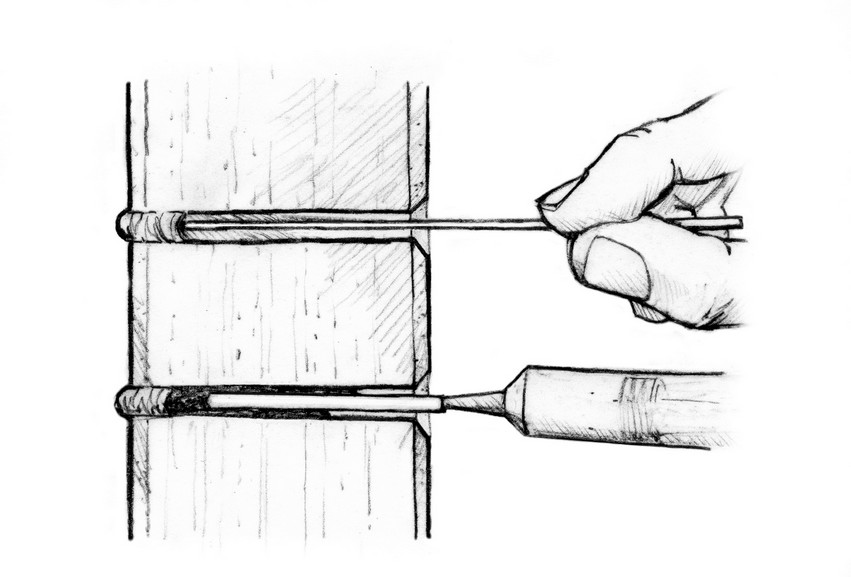

To begin the repair, ream the hole with a drill bit slightly larger than the existing hole to expose clean, fresh laminate and wood. Then chamfer the hole with a countersink. Do this on both sides of the hole if you can reach the backside. The chamfer softens the sharp edge left from the reaming operation so the repair is less likely to telegraph through the final finish. Additionally, when the hole is chamfered on both sides, a mechanical lock is formed when the hole is filled.

In thicker laminates, removing the screw may result in a blind hole, a hole that does not go completely through the laminate. In this case, use a syringe to fill from the bottom of the blind hole. If the hole is deeper than the length of the syringe nozzle, use a soda straw to extend the length of the nozzle. Trying to force thickened epoxy into a blind hole with a putty knife always leaves an air bubble at the bottom of the hole. Filling from the bottom forces all air out of the hole.

Use 404 High-Density Filler or 406 Colloidal Silica Filler to thicken the epoxy. Fiberglass laminate is hard and strong and using 404 or 406 Filler creates a hard, strong epoxy filler, which more closely matches the characteristics of the laminate. A word of caution: These fillers make epoxy difficult to sand. When you fill a hole, clean up around the hole as thoroughly as possible to minimize sanding time.

Follow the standard two-step bonding techniques. First, wet out the hole with neat epoxy. Even though this hole repair example is considered a low-risk repair, any repair that has the potential to allow water into your boat deserves the best possible bonding techniques. You will be able to sleep better at night if the repair is done correctly.

Example 2

A ½” diameter hole passes through the transom below the waterline. The transom has fiberglass skin on both sides of a 2″ thick plywood core. There is no access to the backside of the hole.

This hole has a risk factor similar to Example 1, that is, low-risk, below the waterline. It is low risk because the hole is deep and there is a lot of surface for the plug to bond to. In addition, the hole has very little surface area exposed to the water so there is very little pressure trying to push the repair through the hole. Also, the hole is not located where it will be subject to impact or pounding.

Prepare this hole by reaming and countersinking as described in Example 1. Because there is no access to the inside of the transom, you should install a plug in the hole to keep the epoxy from running through while it is curing. You can make a plug by saturating some type of absorbent material with epoxy and forcing the wet plug to the back of the hole. Cotton balls, foam earplugs, foam rubber from a pillow, paper towel, Kleenex, or any other absorbent material will work. Once the plug is in place and at least partially cured, finish the repair.

Zone 2—Medium-risk repairs using solid wood plugs and fiberglass patches

The next three examples are repaired through a combination of filling with thickened epoxy, bonding solid plugs in place, and using laminates of fiberglass. These repairs fall into the middle of the chart with some higher risks, larger holes, and thinner laminates.

Example 3

A 1″ diameter hole exists in a cockpit seat (lazarette) hatch. It’s a solid ½” thick fiberglass laminate with no core. The topside has a gelcoated non-skid pattern (a type of pyramid). The underside is not an issue cosmetically and is accessible by opening the hatch.

Although the safety risk is low, you want a strong repair to reduce the risk of having the seat crack in use and avoid future repairs. The most difficult part of this repair will be the time-consuming work of matching the color and non-skid pattern of the gelcoat surface after the hole is filled.

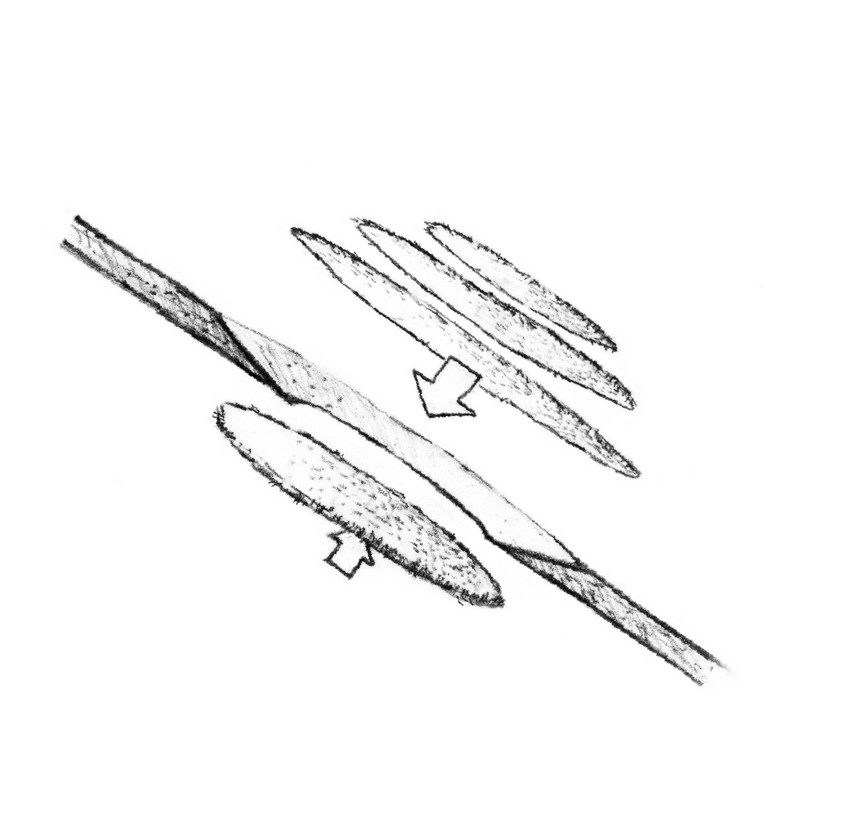

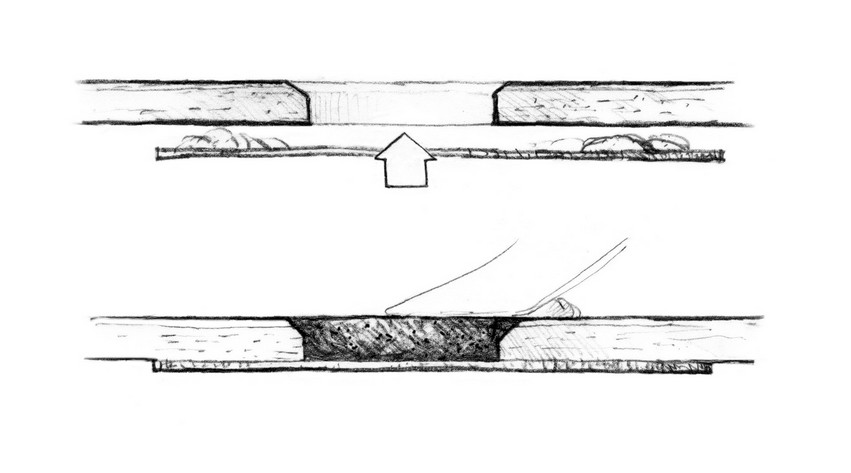

Sand the inside surface of the hole to expose clean laminate. Also sand a 3″ diameter area around the hole, on the underside of the laminate. Chamfer the top lip (the gelcoated side) of the hole, about ½” back, with a countersink bit or a rotary abrasive tool.

Wet out these areas by applying a coat of unthickened (neat) epoxy. Then wet out a piece of fiberglass cloth 2½”-3″ in diameter and apply it to the sanded area on the inside of the hatch. Allow it to cure to a soft gel. Then fill the hole flush with the surface, using epoxy thickened with a WEST SYSTEM™ high-density filler.

If matching the non-skid pattern is important to you, we recommend flexible non-skid mold patterns that are available for molding the exact pattern over the repair.

Example 4

An instrument is eliminated and now a 2″ diameter hole exists in a bulkhead, which is fiberglass with a plywood core.

Although it is a larger hole, this is not a high-risk repair since the hole has existed without weakening the boat and is not underwater.

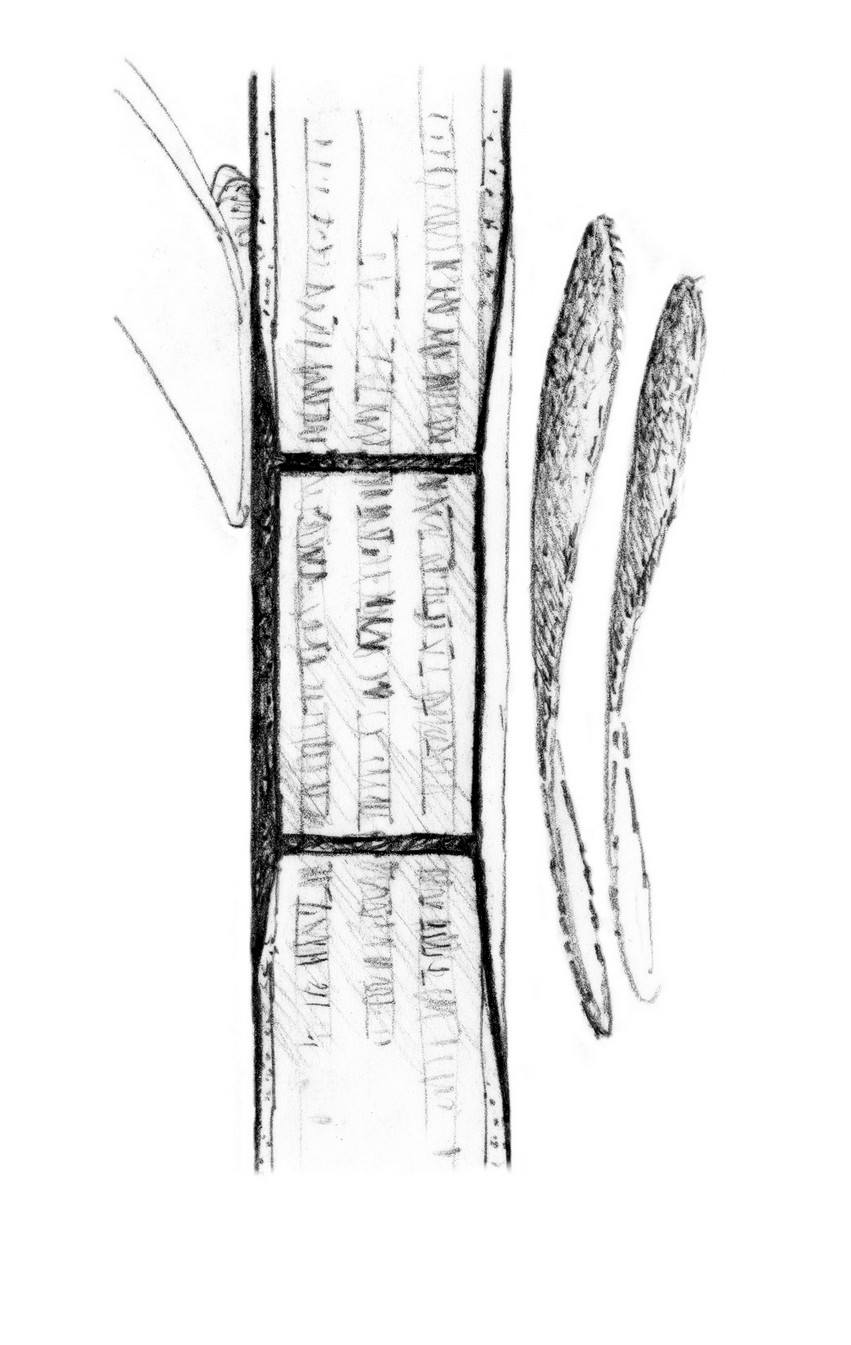

Sand the inside of the hole to expose clean wood. Cut a 2″ diameter wood plug that matches the thickness of the original plywood core. Then dry fit the plug to assure a loose fit. Remove the plug and sand a slight chamfer around the perimeter of the hole on both sides of the bulkhead that flares out onto the fiberglass a ½” or so. Glue the wood plug in place with epoxy thickened with 403 Microfibers. Allow it to cure to a soft gel before filling the low spots on each side of the bulkhead. Fill the low spots on each side of the plug with a layer or two of 6-12 oz fiberglass cloth if the area will be exposed to impact or abuse.

If the area will not be highly stressed, you can fill the low spots on either side of the plywood plug with epoxy thickened with 407 Low-Density Filler or 410 Microlight™. Allow the epoxy to cure before sanding smooth, sealing with a coat of epoxy, and painting or gelcoating. Refer to Finishing, Section 2.2 of the Fiberglass Boat Repair & Restoration manual for information on painting and applying gelcoat over epoxy.

Example 5

A 1″ diameter hole was drilled near the hull bottom through a structural laminated fiberglass bulkhead with a ½” plywood core. Bilgewater should not be allowed to flow through the hole.

Since the repair is to a structural component and needs to be watertight, the consequences of failure are higher than in the previous examples. While it is likely that simply filling this hole will provide enough strength, overlaying the plug with fiberglass will provide more strength and better sealing. What is needed here is to bond in a wood plug that is a bit thinner than the plywood core so that once the epoxy cures you can laminate over it and maintain the original bulkhead thickness.

Fill the hole with a wood plug using the method described in the previous example and then bevel the laminate at a 12:1 ratio on the edges where the new laminate will overlap onto the original. Apply enough fiberglass to match the thickness of the original laminate. Apply paint or gelcoat over the finished surface.

Zone 3—High-risk repairs requiring additional reinforcing

The final three examples describe repair procedures used when a more serious situation would result if the repair were to fail. Each repair uses some form of reinforcing material.

Example 6

3″ diameter hole was mistakenly cut through the ½” fiberglass liner. No access hole exists to the backside.

This repair would meet the criteria in the lower right quadrant of the chart. It is a relatively large hole, and liners are generally thinner laminates even though they often provide a structural component to the hull. While the consequences of a complete repair failure would be quite low, it would still be a good idea to repair this hole by grinding a 12:1 bevel around the circumference of the hole and laminating in a layered fiberglass patch, as described in detail in our manuals.

A backer plate may be necessary to keep the layers in the patch from pushing through the hole. A simple way to make a backer is to wet out a piece of lightweight fiberglass on a sheet of polyethylene plastic and allow it to cure. You can then easily cut this single thickness of glass with scissors to a size larger than the hole and bend it to fit through the hole. Bond this backer plate to the inner surface of the laminate with G/5 Five-Minute Adhesive. You can then lay the fiberglass patch in place without pushing through, squeegee it down and allow it to cure. Then prepare this surface for fairing and finishing.

Example 7

A seacock is being replaced with a smaller diameter one. It is located below the waterline. The hole is 2″ in diameter and through solid fiberglass laminate of ½” thick. The new fitting requires a 1½” diameter hole. Access to the back is good. The bottom is painted with antifouling paint.

In situations like this, where the difference in hole diameter between the old and new hole is ½” or less and the screw pattern for the new thru-hull will be in the original laminate, you can get away with adding minimal reinforcement from one side. To do this, sand the inside of the hole to expose clean laminate, sand the laminate on the backside (4″-5″ diameter area centered over the original hole), and apply the reinforcement. The reinforcement could be a layer or two of fiberglass cloth with epoxy, a thin layer of cured fiberglass laminate like G-10, or a ½” thick piece of plywood sealed with epoxy.

When the epoxy used in your reinforcement has gelled, use epoxy thickened with 403, 404, or 406 filler to fill the hole. After the thickened epoxy has cured, use a hole saw to cut the new hole. Dry fit the new thru-hull fitting, trimming the fiberglass as needed. Use the fitting as a template for locating the new screw holes. Be sure to seal all exposed fiberglass edges and drilled holes to prevent moisture from wicking into the laminate before installing the fitting with a flexible sealant like 3M™ 5200.

Example 8

A seacock that is located below the waterline is being relocated. The hole is 2″ diameter through a solid laminate ½” thick. Access to the backside is good. The bottom is painted with antifouling paint.

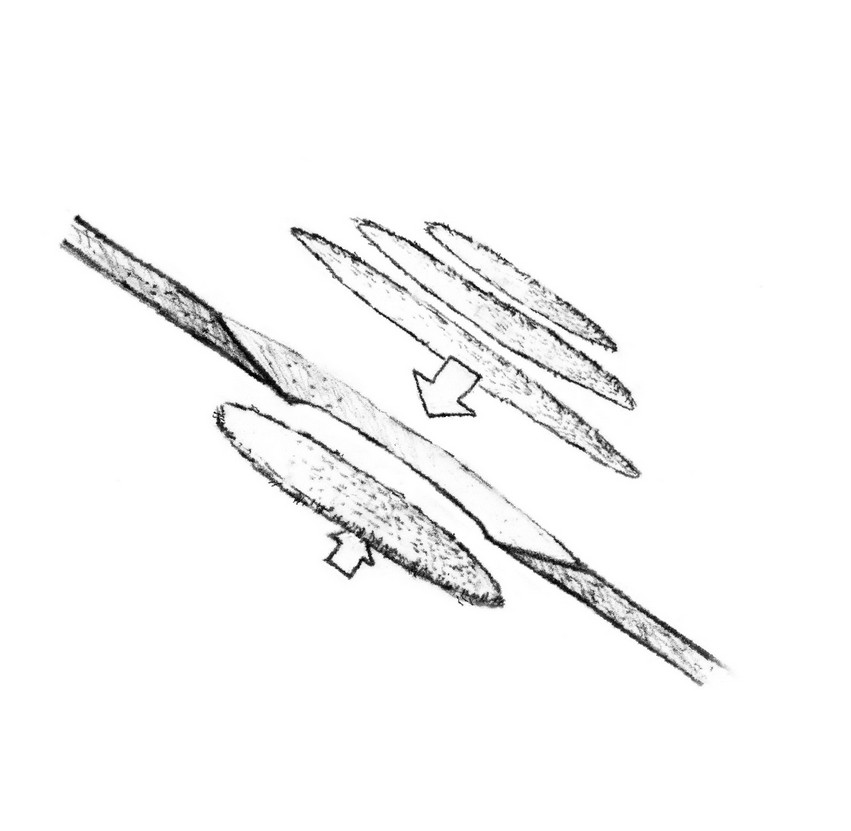

The chart would place this repair in the upper right quadrant due to the hole’s location-a hole below the waterline certainly raises the consequences if it fails- yet, because this is a machined hole and not a puncture or impact hole, the repair should be easy to accomplish. The first step is to sand the inside of the hole to expose fresh laminate. Next, pour some mixed epoxy into a 2″ diameter cup to form a “puck” when cured that is about 1/8″ to 3/16″ thick. Sand the edge of the puck and both face surfaces and then dry-fit the puck in the hole so that it is centered with regard to the thickness of the laminate. You can then bond the puck in by brushing a thickened mixture of epoxy and 406 Colloidal Silica on the inside of the hole and the edges of the puck. If the puck fits loosely and doesn’t stay where placed, use duct tape to hold it in place until the epoxy cures.

Now grind back about 1/8″ to 3/16″ (depending on how thick the puck is) thickness from the laminate on both sides of the hole on a 12:1 bevel. This will give the beveled area about 5″ in diameter. Fill the beveled area on both sides with a layered fiberglass patch and epoxy. Once the patches cure, sand them and an area larger than the patch to prep for fairing and finishing. It is especially important to remove all the antifouling paint anywhere epoxy will be applied because the epoxy will not stick well to most bottom paints.

We hope the chart and the repair methods described in these examples will help you decide how to repair a hole. See also our Fiberglass Boat Repair and Maintenance Manual for information on fairing and finishing as well as laminate repairs. By carefully weighing the particulars of the hole and the importance of the repair, you can make a sound decision on what repair method to choose. This will enable your boat to once again be a hole in the water (with a few fewer holes) into which to pour money!