I’m fast approaching my 22nd year of working here at Gougeon Brothers, Inc. From my first day on the job, I have lived the controversy surrounding penetrating epoxies vs. high-solids epoxies in general and WEST SYSTEM® Epoxy in particular. I have met with the formulator and founder of a popular brand of penetrating epoxy and talked to him many times over the years. He is a nice fellow and passionate about his product, but in the end, we had to agree to disagree.

It only takes a quick search online to find way more information, arguments, and name-calling than any rational person would care to participate in. I’ve never claimed to be rational, so let’s just get right to it.

We are not enamored of penetrating epoxies. In fact, we don’t agree that there’s a need for a penetrating epoxy. At least, not as far as many folks seem to perceive them: “I just want the strongest bond possible to the wood,” or this favorite of mine, “I have dry rot I need to consolidate.” Well, sure, OK, because rotten wood covered in weak, porous epoxy is really very strong–just like new!

I’m sorry for being a bit sarcastic. I couldn’t resist. But I have good reasons to chide. One thing I have to admit is that the manufacturers of the leading penetrating epoxies are masters of marketing. I’m not going to name names, but it’s not too hard to understand if someone believes them when they say, “Our Penetrating Epoxy is made from wood products and so it’s more compatible with wood,” or “Our penetrating epoxy is a ‘high solids’ epoxy.” As ol’ P.T. Barnum said, “There’s a sucker born every minute.”

A quick look at the SDS (Safety Data Sheet) of a penetrating epoxy reveals all you need to know–if you’re a chemist. I happen to be a chemist, and here’s what I found.

A look at Penetrating EPOXY A

One of the best-selling penetrating epoxies, which I’ll call EPOXY A, is fully 69% solvents. That means just 31% of this product is made up of epoxy resin and amine hardener. EPOXY A’s resin and hardener come from typical chemical sources: NANYA, Olin, or any number of worldwide manufacturers. But EPOXY A doesn’t list any of the standard epoxy components like Bis-A resin, polyamines, or nonyl phenol. All they list are the minimum ingredients of hazardous solvents, as required to meet government regulations. The Volatile Organic Content (VOC) is 675 g/ltr, which exceeds the legal VOC limits anywhere in the US. It is possible to legally sell the product because of the first ingredient on the hazardous list, mysteriously called “aromatic hydrocarbon 64742-95-6.” We know how to identify compounds like this by their CAS (Chemical Abstract Service) number. It turns out that the mysterious “aromatic hydrocarbon” is #1 Naptha, commonly known as white gas or Coleman® fuel. #1 Naptha is an exempted solvent. EPOXY A includes enough in its formulation to make it legal to sell in the U.S.

Aromatic napthas are made from coal and coal tars, which come from wood, so there’s a grain of misleading truth in the claim that their penetrating epoxy is made from “natural and earth-friendly” sources. The problem is the “natural” or “wood-derived” part of EPOXY A is from solvents like Naptha and isopropyl alcohol, not the epoxy portion as implied.

Naptha penetrates wood cells easily. Unfortunately, this solvent also separates from the epoxy, so the epoxy does not move into the wood along with the solvent front.

A look at Penetrating EPOXY B

Now let’s look at EPOXY B, a newer “high-solids” penetrating epoxy on the market. The claim “high-solids epoxy” implies two things: First, that the product is not solvented, and second, that it’s as strong as true high-solids structural adhesive epoxies like WEST SYSTEM and others.

The SDS of EPOXY B is more detailed than that of EPOXY A, but it reveals an epoxy resin and hardener content in only the 40%-60% range. The other ingredients—while not nearly as flammable, toxic, or nasty as the solvents in EPOXY A—are considered non-reactive diluents, meaning they don’t react with the solids in epoxy or become part of the cured epoxy matrix. EPOXY B does not constitute a true high-solids epoxy.

What EPOXY A and EPOXY B have in common is poor moisture exclusion properties. Some of these solvents have long-chain molecules and since they are non-reactive and/or volatile, they will find their way out of semi-cured and even cured epoxy coatings. This leaves behind “wormholes” which water, with its small H2O molecule, can easily penetrate.

While I would expect EPOXY B to be somewhat better at moisture exclusion than EPOXY A, neither can compare to unsolvented WEST SYSTEM epoxy.

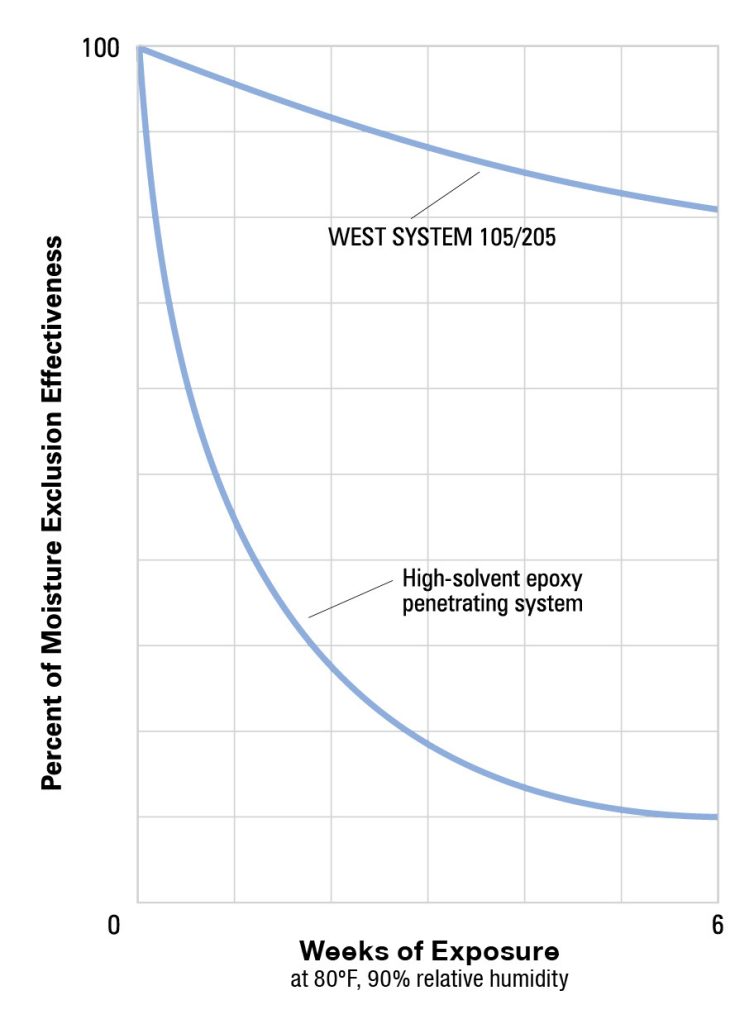

We did a test to compare the moisture exclusion properties of penetrating epoxy and 205. The test is done by coating coupons of prepared and dried plywood with 3 coats of 105/205 or high-solvent epoxy (EPOXY A), then measuring the weight gain when exposed to a 80°F/90% relative humidity environment over time. The graph should be understood as follows: The high-solvent epoxy (EPOXY A) coupon gained 90% weight. This is more than four times the amount of moisture absorbed by the 105/205 coupon. Obviously, solvented, penetrating epoxies are not effective moisture barriers, with only 10% effectiveness after six weeks of exposure.

Getting Soaked

What about the epoxy “soaking in” deeper for better adhesion? WEST SYSTEM and other true high-solids, quality epoxies have never relied on so-called deep penetration to make an effective bond. Our products provide strong, effective bonding and moisture-resistant coating that keeps the wood’s moisture content stable. Dry wood is strong wood. The basis of our philosophy is that wood makes an excellent structural engineering fiber when it’s kept dry. We have 47 years of history to back this up. A prime example is Meade Gougeon’s 35′ trimaran Adagio, launched in 1970. Adagio is arguably the oldest wood/epoxy structure on the planet, and not a drop of penetrating epoxy was used in her construction or maintenance. The important thing to remember is this—to create an effective moisture barrier, the epoxy does not need to penetrate deep into the wood. WEST SYSTEM Epoxy, as well as other full solids epoxy adhesives, penetrate deep enough to force wood failure in both tensile adhesion and shear stress tests.

Maximum Penetration

Over the years we’ve learned a couple techniques to get maximum penetration using standard WEST SYSTEM resin and hardeners. The first is to simply use the 209 Extra Slow Hardener—the longer open time of 3-4 hours as opposed to 90–110 minutes for 206 Slow Hardener allows the epoxy to soak in more.

Another way to maximize penetration into wood is to heat the wood first. Get it a good 30–35°F hotter than ambient temperature with a heat lamp or heat gun. As the wood heats up, the air inside the wood cells expands and escapes. This is called outgassing. So heat the wood and mix your epoxy. When the wood gets to temperature, remove the heat source and apply the epoxy to the cooling wood. Two things happen: when the epoxy hits the hot surface, its viscosity drops. Then, as the wood cools, the air in the cells contracts, pulling the thin, warmed epoxy with it. Keep in mind, heating the epoxy will shorten the open time.

Comparison Test

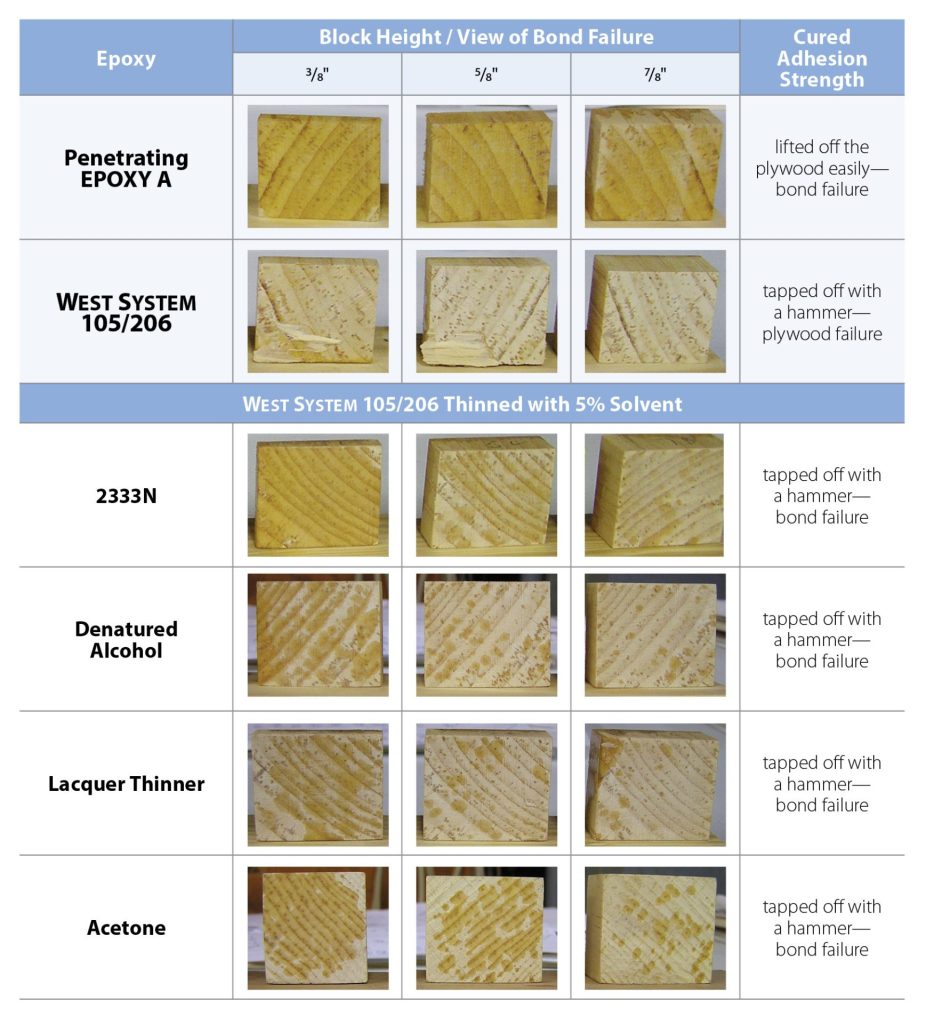

I did some comparison testing of EPOXY A and WEST SYSTEM, adding various solvents to WEST SYSTEM 105/206 at 5% by weight. We used clear Douglas fir blocks at 3/8″, 5/8″, and 7/8″ thick, cut from the same board with the grain running through the thickness, like end-grain balsa. I weighed 10g of mixed product and applied it to the tops of the blocks. The blocks were set on pieces of plywood while the epoxy migrated through the block and into the plywood before curing. All of this was done at room temperature (~72°F).

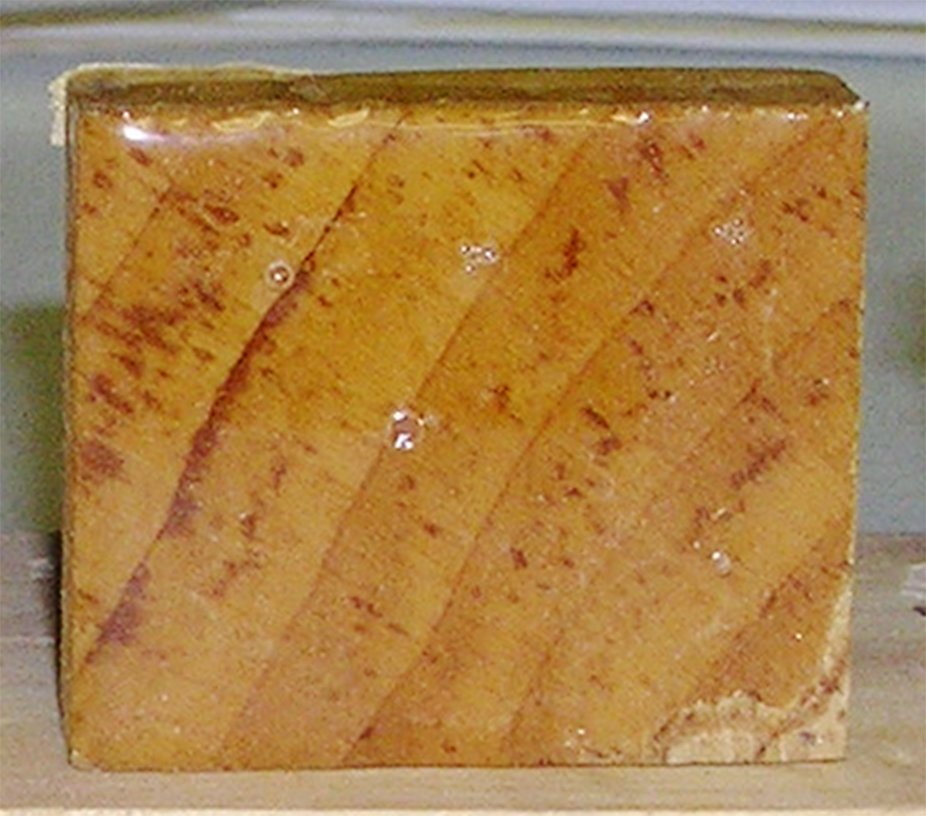

Above, we see WEST SYSTEM 105/206 and EPOXY A. First, we see the shiny coating of 105/206 on top vs. the dull top of the EPOXY A blocks on the bottom. In the test result table below, the bottom of the EPOXY A blocks look just like the tops for the most part, vs. the bottoms of the 105/206 blocks with dots of epoxy that made it through to the end grain. This might lead one to think the EPOXY A really did penetrate deeper into the wood. But does it? Despite appearances, the EPOXY A blocks lifted off the plywood easily–no adhesion at all. Had any epoxy solids made it through, it should have bonded somewhat to the plywood. But it did not.

On the 105/206 blocks, even though it looks like less epoxy made it through, enough came through to force wood failure (rather than glue line failure) of the plywood it sat on. These samples had to be tapped off with a hammer.

Conclusions

These results support my long-held theory that in so-called penetrating epoxies with a high solvent content, the epoxy portion does not move through the wood with the solvents. My theory is further supported by the fact that none of the solvented examples of WEST SYSTEM 105/206 failed the plywood base in the way that the unadulterated WEST SYSTEM si. They had to be tapped with a hammer, indicating some of the epoxy moved with the solvent front, but not enough epoxy to fail the plywood surface. Keep in mind, this happens with only 5% solvent added to WEST SYSTEM 105/206. Meanwhile, EPOXY A contains 70% solvent, and EPOXY B is at least 40% diluent and could be as high as 60%.

As you can see below, the wet or stained areas appear pretty large in the WEST SYSTEM samples. But again, not enough structurally high-solids epoxy penetrated through these blocks to glue them to the plywood.

In conclusion, only the unsolvented WEST SYSTEM 105/206 was strong enough to cause the plywood base to fail. I toss the question back to those who support the notion that penetrating epoxies are the cat’s pajamas. Cats don’t really wear pajamas, do they?