by Brian Knight—GBI Technical Advisor

Fixing damaged or delaminated stringers is one of the most common repairs associated with fiberglass boats. The usual causes of stringer failure are disintegration of the stringer core material, impact damage from slamming and grounding, and fatigue from normal use. Although each repair situation has its own unique problems, the following techniques are fundamental to stringer repair. These guidelines will help you repair almost any damaged stringer. Remember, stringers are structural support members. As you repair or replace damaged material, use your best workmanship.

Typical stringer construction

Stringers are support members bonded into boat hulls, usually oriented parallel to the long axis of a boat hull. They are there for a variety of reasons. They stiffen unsupported flat hull sections, they support cockpit and cabin soles, and they distribute high load concentrations from engines and other mechanical systems. Often, they perform several of these functions simultaneously.

In fiberglass boats, you will find that most often, stringers are composed of a core material overlaid with a fiberglass skin. The skin usually extends a few inches on either side of the stringer. This skin extension, or tabbing, ties the stringer to the hull or bulkheads and spreads the load of the stringer over a larger area. Tabbing may be a simple piece of glass tape across the stringer/hull joint, or an integral structural part of the stringer. Some cores are structural, or active, and some are inactive, used primarily to provide a form for a structural fiberglass skin.

With active core stringers (usually solid wood or pressure-treated plywood), the core material provides the stringer with most of its structural strength. Generally, the more dense the core material (like wood or plywood), the more of the load it is expected to carry. The fiberglass skin covering an active core is primarily used to protect the wood and to attach it to the hull. It is generally thinner than the skin on inactive core. When you replace structural cores, you have to use proper scarf bevels or other proper means of piecing the new core into the old.

Occasionally, you will find a material that at first glance appears to be plywood, but on closer examination, you will find that all the veneers are oriented in the same direction. You cannot repair this unidirectional material with plywood. Plywood has half the grain running at right angles to the face veneer. It does not have the same strength as unidirectional material. A common example of unidirectional plywood material is called laminated veneer lumber (LVL).

Low-density core material is non-structural, or inactive. A low-density core depends on the fiberglass skin to carry the loads. Inactive cores are made of low-density foam, cardboard tube, or in the case of molded stringers, no core at all. Occasionally, stringers are pre-built in a mold and tabbed in after the hull is built. This type of stringer has no core material, just fairly heavy fiberglass skins to provide the structural strength.

Assess the damage

Before you start any repair, it is a good idea to know what you are getting into. Looking at the suspected area of damage may be as easy as opening a hatch, but don’t count on it. Hull liners are common and usually fastened to the very stringers you are trying to fix. It is also difficult to see under engines, water tanks, and the like. You may have to cut access holes in the hull liner or cabin sole to see the area in question. Fortunately, you can purchase access covers to fill the hole.

Once you have resigned yourself to cutting holes in your boat, use a mirror and flashlight and look for the following:

Impact damage

Look for obvious fractures in the stringer. Also, look for delamination of tabbing and core away from the impact point. Inspect the tabbing where the stringer attaches to a bulkhead or transom.

Rot damage

Wood cores rot from water leaking around fasteners and from water collecting where the fiberglass skin has delaminated. You can often tap the suspected area of stringer with a small hammer. The impact of the hammer has a definite “dead” sound where the core is not firmly attached to the fiberglass.

Repairing local core damage

For small areas of rot, dry and inject epoxy. While this is a common method of wood stringer repair, it is not nearly as effective as replacing the damaged area with wood. Without removing the skin from the wood, it is often difficult to determine the extent of the rot. Also, the degree of penetration of the injected epoxy cannot be accurately determined, so you do not know how good your repair is. If, however, you choose to use this method, we recommend the following procedure:

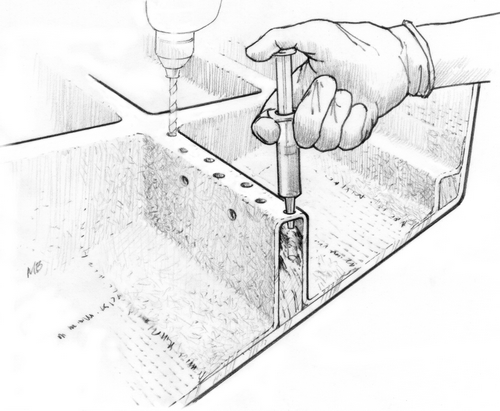

- Drill a pattern of 3/16″ diameter holes over the rotted area. Space the holes 1″ or less from center to center in all directions. Drill each hole deep enough to pass through the rot, just into solid wood.

- Dry the area thoroughly. If necessary, use heat guns or fans to accelerate drying.

- Inject or pour resin/hardener mixture into the holes while the core is warm. Epoxy will be warmed by the core. It will become thinner and penetrate more deeply into the exposed end grain. 206 Slow Hardener should penetrate more deeply than 205 Hardener before it begins to gel.

- Continue to add epoxy to the holes until the wood can no longer absorb more.

- Fill remaining voids with thickened epoxy after the injected epoxy reaches its initial cure, if necessary. Use an epoxy/low-density filler mixture for cosmetic fairing of the surface.

Repair guidelines

For more serious repairs that involve removing and replacing stringer material, try to duplicate the original construction. Unless the damage is directly attributable to an undersized stringer, assume that the stringers were structurally adequate and properly located when the boat was originally built. Making a repair that is significantly stronger than the original design can cause hard spots, which may distort or crack the hull shell. A repair that is lighter than the original may fail prematurely. When removing and replacing stringer material, observe the following guidelines:

Duplicate the shape and dimensions of the original stringer

Where the stringer is supporting a cockpit, or cabin sole, or engine, the height of the repaired or replaced stringer must be the same as the original. If not, you will have a great deal of difficulty reinstalling the equipment.

Duplicate the original core material or find an equivalent material

Use wood where wood was used, plywood for plywood, foam for foam, etc. Attempt to duplicate the species of wood used in the stringer as well as the dimensions of the wood. You can use a more cavalier approach to replacing low-density core materials than you can for active cores.

Measure the thickness of the fiberglass skin and duplicate it

On stringers with an inactive core or molded stringers (with no core), watch for variations in the skin thickness. Occasionally, the top skin of the stringer is thicker than the side skins. This “cap” can significantly increase the strength and stiffness of the stringer. If the extra thickness is present, try to duplicate it.

Locate new stringers as close as possible to their original position

This is especially true of engine stringers or stringers that support other equipment.

Support the hull

If major stringer replacement is necessary, be sure to support the hull well so the original shape is maintained. Stringers that are removed or have broken away from the hull may allow parts of the hull to sag.

Replacing active core sections

Often damage to the core of a stringer is limited to a small section, or the stringer may be too difficult to remove. You may be able to replace only the damaged portion, restoring the strength of the stringer while leaving it in position in the boat.

Because the wood in wood-cored stringers is structural, any repairs you make to it have to be joined with a proper scarf. If you are replacing a section of plywood stringer, use a minimum of an 8-to-1 scarf bevel. For a ¾”-thick piece of plywood, this equates to a 6″ long bevel. When repairing hardwood or highly loaded core areas, use a longer (12-to-1) scarf angle. When cutting scarfs, keep in mind, the longer the scarf angle, the greater the joint surface area, the stronger the joint. All joints in fiberglass skins should have a 12-to-1 bevel or overlap.

Forming the scarf bevel on the new piece of wood is fairly easy. You can use typical cutting tools with the piece of wood supported on a workbench. Cutting the matching bevel on the wood that remains in the boat is not as easy. You will need to be creative. You will use chisels, disc grinders, hand planes, hand saws, and anything else you can think of to cut wood and fiberglass. The surface of the bevel does not have to be perfect. The epoxy that you use to glue the joint is an excellent gap filler.

- Cut out the damaged section of the existing stringer. Remove as much skin as necessary to remove all of the damaged core. Trim the exposed core ends to a minimum 8-to-1 scarf angle.

- Grind the edges of the skin to 12-to-1 scarf angles to prepare for the skin replacement.

- Trim a new piece of core material to fit the size and shape of the void in the existing core. Use the same species of wood as the existing core. Cut a matching scarf angle on each end of the new core section. Dry fit and trim the new piece and existing core ends as necessary for a good fit.

- Prepare the surfaces for bonding. All surfaces should be clean, dry, and sanded.

- Install the new core section. Wet out all contact surfaces of the new and existing core. Apply a liberal amount of thickened epoxy/406 mixture to one side of each contact area.

- Clamp the section in position. Clean up excess epoxy before it cures. Remove clamps after epoxy cures thoroughly.

- Replace the fiberglass skin as described later.

Replacing stringers

Completely replacing a stringer is often easier than replacing a section. For example, engine stringers commonly run from the transom to a bulkhead. They may not run the entire length of the boat. Complete replacement of the damaged stringer may be much easier than attempting to replace a section of it.

- Mark the location of the outside surfaces of the stringer. It is often critical that the stringer gets replaced in exactly the same position it was previously located. When you remove the old stringer, you will need reference points to locate the new one. Locate the reference marks far enough away from the repair area so they will not be disturbed when you prep the area.

- Remove the stringer and core. Save any large pieces of core you remove. They make great patterns and will speed up fitting the new core. Measure the thickness of the fiberglass skin so you can duplicate it.

- Using the same species of wood as the existing core, trim a new piece of core material to fit the size and shape of the core in the removed stringer. Dry fit and trim the new piece for a good fit.

- Prepare the surfaces for bonding. All surfaces should be clean, dry, and sanded.

- Wet out all contact surfaces of the hull and core. Apply a liberal amount of thickened epoxy/404 High-Density or 406 Colloidal Silica mixture to one side of the contact area.

- Push the stringer in position with firm hand pressure. The epoxy mixture should squeeze out of the joint. Brace or tape the stringer in position as necessary.

- Shape the squeezed-out epoxy into a fillet. Apply additional thickened epoxy to the joint if necessary for a smooth ½”-radius fillet. Clean up excess epoxy before it cures. Remove clamps after epoxy cures thoroughly.

- Replace the fiberglass skin as described later.

Replacing or repairing the fiberglass skin

After repairing or replacing core material, it is necessary to replace the fiberglass skin. To duplicate the strength of the original skin it is important to duplicate the thickness of the original skin and to properly prepare the surfaces for a good bond.

Preparing the fiberglass fabric

Measure the thickness of the skin on the original stringer. Keep in mind, the top skin may be thicker than the sides and the tabbing. Refer to the chart to determine the number of layers of a particular weight fabric necessary to achieve the thickness required.

Cut the necessary number of strips of fiberglass fabric to the length of the stringer. The first piece should be large enough to extend as far as the original tabbing from each side of the stringer. Cut each of the remaining pieces 1″ (½” each side) narrower than the previous one. When laying out the layers of fabric, do not allow the tabbing edges to end at the same place. For stress reduction, step the edges of the fabric to create a tapered edge. If you fail to do this, all the load the stringer is carrying will be transferred to the line on the hull surface where the tabbing ends, and the hull may crack at that point. If, however, you step the tabbing edges, the load from the stringer is gradually distributed to the hull. Where stringers end at a bulkhead or the transom, wrap the glass tabbing onto them in the same manner.

WEST SYSTEM 738 Fabric is ideal for stringer repairs. It yields about 0.040″ per layer in a hand lamination, so you will need fewer layers of cloth to achieve the necessary thickness for most stringers. Fewer layers of fabric translate into less labor to install them. There is, however, nothing wrong with using a lighter fabric. It will require more layers per unit of laminate thickness and thus more time to install it. Structurally, there is little difference between 5 layers of 24 oz. fabric or 10 layers of 12 oz. fabric.

Preparing surfaces for bonding

Surface preparation for bonding is a critical part of any repair. The bilge of a boat can be very difficult to prepare for bonding, because it is likely to be contaminated (especially around engines) and many areas may be inaccessible.

Use a degreaser or detergents in areas that may be contaminated with gasoline or oil residue before wiping with solvent. Use a stiff brush on heavily textured surfaces like roving. Remove any traces of contamination by wiping the surface with solvent and drying with paper towels before the solvent evaporates.

Use a 50-grit grinding disc to prepare the surface. 50-grit cuts quickly with little heat build-up. If gelcoat is present and it is soundly attached, you do not need to remove it. Grind it to create a fresh, no-gloss surface. Brush the area free of dust or loose material. Use a wire brush to abrade heavily textured surfaces. The bonding surface should appear dull. A 12-to-1 bevel must be ground into any existing fiberglass left on a stringer. The new fiberglass will run onto this bevel, attaching the new material to the original material. A 12-to-1 bevel provides adequate surface area for the transfer of loads across the repair area. For example, if the skin on the original portion of the stringer is ¼” thick, the bevel needs to be 12 x ¼” or 3″ wide.

It is difficult to form fiberglass cloth around a sharp 90° bend. You have to create radius at the top edges of the cores and fillet at the core/hull and core/bulkhead inside corners—a 3/8 – ½” radius is a good starting place.

Applying the fiberglass skin

- Prepare fiberglass fabric and bonding surfaces as described above.

- Wet out the entire bonding surface, including the stringer, with a mixture of resin/hardener. Squeegee a thin layer of thickened epoxy over the exposed panel bonding area if the surface is heavily textured. Mix epoxy/404 High-Density or 406 Colloidal Silica filler to the consistency of mayonnaise. The thickened epoxy will fill voids on the surface and provide better contact with the first layer of fabric.

- Center the largest piece of fabric over the stringer and reinforcement area and wet it out with the resin/hardener mixture. Squeegee any excess epoxy from the surface, making sure the entire piece of fabric has been saturated.

- Apply each successive piece of fabric in the same manner. Successive pieces may be applied immediately after the previous piece or any time before the previous piece reaches its final cure (ideally while it is still tacky). The fabric edges should be stepped, with the last piece extending about 1 ¾” to 2 ¼” from each side of the stringer (depending on the number of fabric layers). Allow the lay-up to reach its initial cure.

- Apply two or three coats of epoxy before the lay-up reaches its final cure. To avoid sanding between coats, apply each coat before the previous coat reaches its final cure. Allow the final coat to cure thoroughly.

Note: The final two or three coats may be tinted with WEST SYSTEM 501 (white), 502 (black), or 503 (gray) pigment or with 420 Aluminum Powder (gray). If you desire a smoother cosmetic finish, the lay-up may be faired and finished.

When your repair is complete, you will have a little additional finishing work to do. Fiberglass repairs inevitably have some sharp edges or sharp “hairs” sticking out. These make cleaning the bilge difficult if not downright dangerous. It is a good idea to use some 80-grit sand paper to eliminate the imperfections that might cut you.

You have a couple of options for final finishing:

- Do nothing. Since most of the work is in the bilge area, you do not need to apply a final finish. UV degradation of the epoxy will not be a problem, and in many circumstances, the appearance of the repair does not matter.

- Paint the repair. If the appearance of the repair matters, select a paint color that matches the rest of the area and paint the repair. Proper surface preparation of the repair includes washing with water and thoroughly sanding the epoxy surface. Apply a paint primer or apply the topcoat directly to the prepared epoxy.

As always, when you’re installing any hardware, use epoxy to seal all holes you drill. If you neglect this step, you will likely have another repair job in a few years when the core material rots.