For a Polynesian Voyaging Canoe

By Joe Parker

The John Williams Boat Co. (JWC) on Mt. Desert Island, Maine, recently a set of iakos for the Polynesian voyaging canoe Hôkûle’a, built and maintained for the Polynesian Voyaging Society. We sailors sometimes think of ourselves as adventurers and explorers, self-sufficient and capable of handling the vagaries of wind and weather. But our view of voyaging includes refrigeration to keep the food and drink cold, sail handling and navigation systems to make sailing easy and safe, and a good dry, comfortable boat so we remain content while sailing to the ends of our own personal world. When we compare that to the skills and equipment of early voyagers, it can be almost embarrassing.

This project helps put this into perspective. The Polynesian voyagers were considered the best navigators of all time, finding their way around the Pacific Ocean from island to island without manmade navigational tools or equipment. No compasses, no charts, no timepieces. Their techniques have been passed down through many generations and studied by the brightest minds in science to figure out how they were able to accomplish this remarkable feat.

Hôkûle’a is a traditional twin-hulled voyaging canoe replica launched in 1975 to continue the tradition of voyaging throughout the Pacific. She will be rebuilt using traditional methods as much as possible. All structural members will be lashed together and no fasteners will be used to reassemble the craft. When complete, this restoration will allow the boat to voyage around the world. The goal is to circumnavigate the globe using only the traditional methods passed down by the Polynesian navigators. Many articles, books and TV documentaries have been produced chronicling this mission. This article is primarily about the portion of the project completed by the staff at John Williams Boat Co. in Maine that will help make the voyage a reality.

Bill Wright, Project Manager at JWC, approached us about a year ago for help with some details necessary to build the boat’s iakos. The iakos are the beams that hold the twin hulls together and provide the structure for the entire sailing and living platform. The original beams were carved from single trees, but the scarcity of the appropriate timber makes replacement with one-piece beams nearly impossible.

The most appropriate solution was to build laminated beams. This presented a unique set of challenges.

The decision was made to use white oak for strength, stiffness and rot resistance. However, white oak is notoriously difficult to bond too. Sample laminates were made with WEST SYSTEM® G/flex® epoxy as well as a competitive product to compare performance and to examine the suitability of the concept. These test specimens were sent to the Advanced Engineered Wood Composite testing facility at the University of Maine for a complete evaluation.

The G/flex epoxy performed admirably in the structural testing at AWEC, providing the confidence needed to proceed with the project.

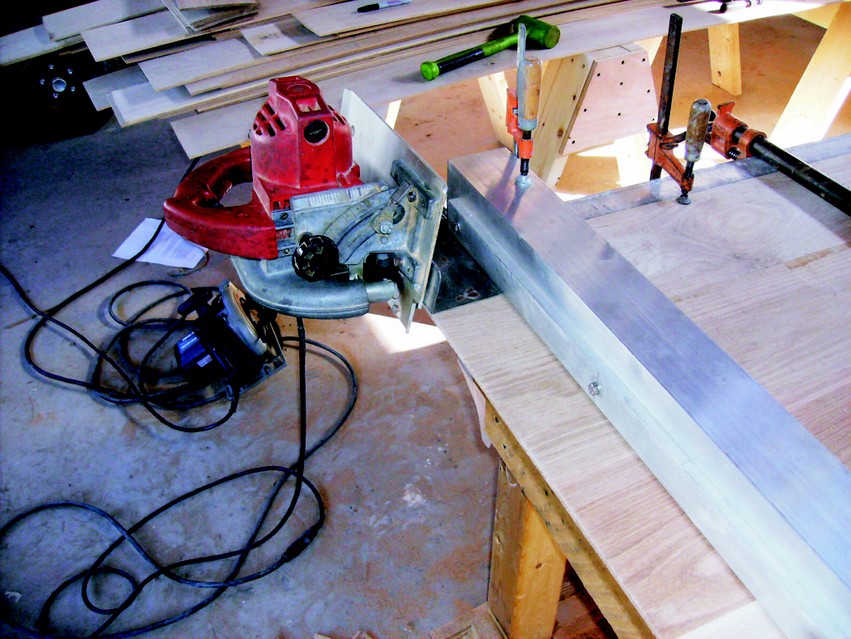

The next hurdle was to determine how to build these large beams with a fairly complex shape. A steel mold or strongback was fabricated along with some integrated clamps to allow molding each beam in just one laminating session. These beams are approximately 20′ long and the cross section is 5½” × 5½”.

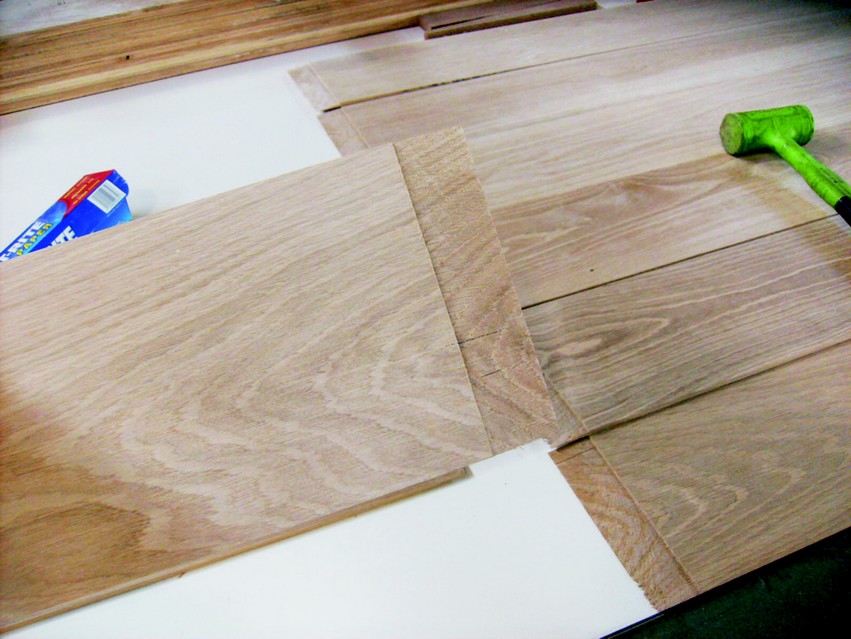

The prep work for the glue up operation took days. This work included accurately machining all the veneers to a uniform thickness over their full length, and a dry run to ensure the sawn white oak veneers would conform to the mold shape in the full stack. The white oak stock was re-sawn, planed and sanded to ¼”-thick, so twenty four plies had to be scarfed to get the full length stock. Once that was complete, mixing the G/flex adhesive and applying it to the entire lay-up took less than an hour.

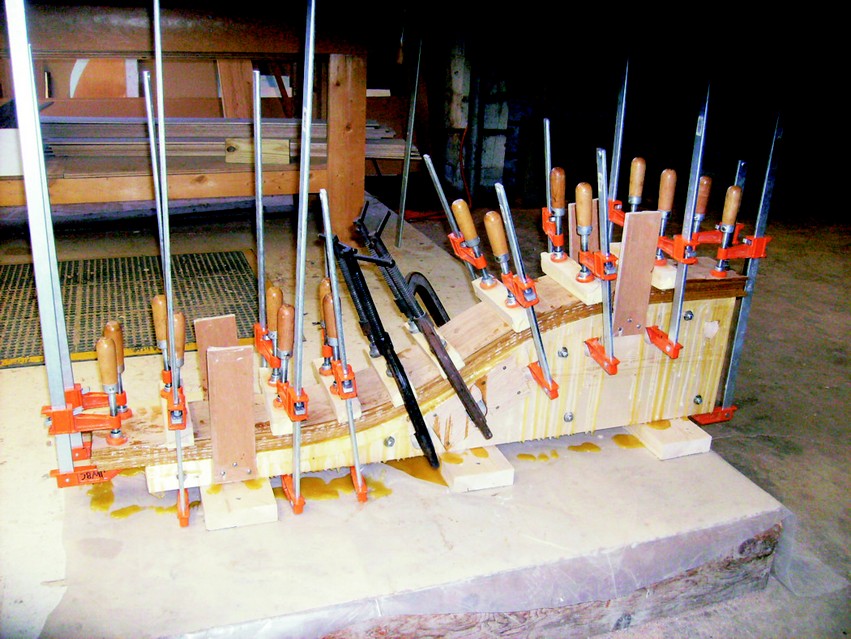

Perhaps the biggest challenge was getting sufficient clamping pressure in some areas of the beam laminate while not squeezing out too much adhesive in other areas. To prevent this from happening, the G/flex 655 was mixed and applied to all mating surfaces. A thin coat was squeegeed onto one surface and a thicker coat was applied with a notched trowel to the other mating surface. Then the plies were stacked onto the mold.

It was equally important to keep clamp pressure on as the plies were drawn down. Clamps were tightened near the center of the beam first, then pressure was progressively applied moving toward the ends of the beam. This helped eliminate dry spots that could occur if pressure was applied, released and reapplied.

The testing at AWEC indicated that the coated test sections held up to the moisture cycling ninety percent better than the un-coated sections. So, once the G/flex epoxy was cured, the surfaces were planed and sanded to prepare for the multiple coats of WEST SYSTEM 105 Resin® with 207 Special Clear Hardener®.

This is a perfect example of spending enough time preparing the stock, building an appropriate mold, arranging the clamps and tools and finally, when everything is truly ready, building the part. There is very little risk in a project like this if it’s properly managed.

The result is pretty impressive. These one-piece laminated beams are very large, very rigid, and should allow the voyaging canoe Hôkûle’a to sail around the world confident her structure is solid.