by Meade Gougeon — GBI Founder

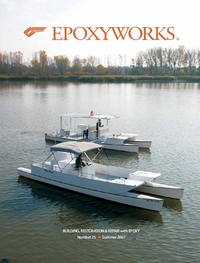

Above: Meade and Jan’s completed Gougmarans, shallow-draft power catamarans on Dick Newick-designed hulls.

In 2003, my brother Jan and I began talking about building a motorboat. This would be a first for the brothers, who up to this point have focused all our efforts on sailboats. Just a few years ago, it would have been inconceivable that we would ever take up powerboating. But time and circumstances change one’s views, especially as we enter our senior years. We have always regretted that major parts of our home waters, the Saginaw Bay of Lake Huron, Michigan, have been too shallow for our sailboats. Some of the most attractive parts of the Bay with the best wildlife have been off-limits to boats that draw more than 18 inches.

Then we both acquired winter residences on St. Joseph’s Sound, which extends from Clearwater Beach north 12 miles to Tarpon Springs on the west side of Florida. This shallow body of water features a series of protective barrier islands that are uninhabited with sandy beaches and abundant wildlife, some out as far as five miles. The islands are popular destination points, but we needed the proper craft that could transport a crowd of people over these shallow waters and land them safely on the beaches.

We were also attracted to potential cruising. Much of the west coast of Florida is off-limits to larger powerboats with a normal draft, as they must stay within the dredged inland waterway that runs from Tarpon Springs down to Marco Island, where the Everglades begin. Most sailing is done out into the Gulf. If one wants to really explore the west coast of Florida including the Everglades, the shallowest possible draft would be necessary.

With our minds focused on both our summer and winter waters, we began to establish a set of design criteria for our new craft. These can be summarized as follows:

- Achieve lowest possible draft.

- Use the best high-tech sailboat technology to build the lightest weight structure possible.

- Build for maximum seaworthiness to withstand higher winds and waves encountered in coastal waters.

- Build the largest boat possible that can be practically trailered behind a Honda Odyssey ™ van, with all up boat and trailer weighing no more than 3,000 lb.

- Achieve high efficiency with maximum mileage per gallon of petrol. Speed would be secondary to efficiency, with lowest noise and vibration from the engine. Incorporate fuel tanks to support a reasonable cruising range.

- Carry a load of up to 2,000 lb at reasonable efficiency.

- Develop a “landing craft” type of front end that can be lowered for easy passenger offload.

- With the addition of auxiliary live bait well and rod holders, provide a first-rate fishing platform.

- Have a stand-up enclosed head.

The Gougmaran Hulls

Based on our earlier success with the Gougeon 32 sailing catamaran, we quickly decided on a two-hulled catamaran configuration of about 32′ length with a trailering capable width. The project got a time-saving boost when we discovered that some ideal hulls that could fit our needs already existed. Famed multihull designer Dick Newick had designed some 32′ hulls for Still Water Marine that were incorporated into a powered catamaran configuration to function as chase boats for rowing shells. The design goal had been for a craft that could follow an 8-man rowing shell at speeds up to 15 mph with minimum wake. We knew that low wake equates to high efficiency, so we called Dick, a long-time friend with whom we have collaborated on many projects. Dick sent us design details, which showed hulls with a high prismatic coefficient together with a low wetted surface, further suggesting high efficiency. Of equal importance was the fact that each hull was capable of supporting 2,000 lb at a little over 11″ draft. This was perfect for our needs of a fully loaded craft at 3,500 to 4,000 lb with less draft than we initially believed would be possible.

We quickly struck a deal with Dick Perelli, president of Still Water Design, to build us four hulls in his existing molds to our specifications using our Pro-Set® Resins and the vacuum-bagged laminate schedule that we had developed for our G-32 sailboats some years before. We took delivery of these hulls in February 2004 and were delighted when they weighed in at slightly less than 200 lb each. We were off to a good start and only needed to get the rest of the construction right to reach our goals.

Gougmaran Assembly

We began by building a large, mostly flat, deck mold that had a pronounced curve forward. This would be the front of our anti-dive/wave deflector for safe handling in a rough seaway, especially downwind. The mold was constructed of simple plywood over frames and stringers made airtight so that a vacuum bag could be utilized for compaction. The deck laminate measured about 22’×8’6″ and was to be made in one piece in a gentle curve that fit the gracefully curved sheer line of the hulls. The laminate itself was composed of two pre-scarfed panels of 3-ply okoume plywood. The upper panel was 5 mm and the lower panel was 4 mm with a 1½” honeycomb core separating the two completed panels. This laminate was the largest and heaviest part of the structure.

With appropriate framework and beams incorporated within, it was estimated to weigh close to 350 lb when completed. Meanwhile, the hulls were prepared for final assembly into a catamaran configuration. Fore and aft main bulkheads and robust sheer clamps with maximum gluing area were installed. The hulls were then set in their proper location for joining, and a trial dry fit with the deck took place. When a proper fit was assured, we did a massive one-shot gluing operation with our slowest setting Pro-Set® Adhesive1.

When the cure was completed, after several days, the joined hulls proved to be incredibly rigid with the deck laminate serving as a giant torque box. At this point, we estimated our beginning catamaran structure at around 800 lb; we were right on our target for an all-up weight of 1,500 lb for the finished craft. We then joined a second set of hulls and deck for brother Jan’s boat. These benefitted from the learning curve, being a little lighter. Other than that, they were an exact duplicate of the first.

Alternate Approaches

From this basic platform, Jan and I had different ideas as to what to build to suit our individual tastes and needs. I wanted a protected steering station that could keep one out of the sun and weather with a permanent top to which we could lash canoes or windsurfers. I also envisioned a framework that could support an awning and a large tent for cruising. This all came at the expense of weight and windage. Thus, Jan favored a smaller steering station with a windshield and traditional fold-down bimini. Jan also wanted permanent side panels for looks and to keep the beer cans from blowing away. Because of the extra weight of my steering station and upper structure, I opted to use a weight-saving traditional sailboat lifeline system around the boat perimeter; this has worked surprisingly well.

The Engine

Weight placement, we learned long ago on our sailboats, is all-important to maximize the efficiency of displacement hulls. We began by placing the engines forward of the transoms by 4’6″. The steering station, fuel tank, battery, and storage were also placed well forward, and the anticipated weight was carefully balanced over Newick’s designed waterline. We chose an 18-gallon tank to give us a reasonable cruising range. Fully fueled, it weighed just under 200 lb.

The chosen engine was a three-cylinder 30 hp Yamaha™ 4 stroke. This high torque, low rpm engine turns a large 12″ diameter prop with a 9″ pitch. It has proved to be a good marriage with Newick’s displacement hull design. Both engine and hull seem perfectly tuned at 12 to 15 mph, dependent on wind and wave direction. At this speed, the engines are unusually quiet and smooth and the hulls seem to be in their maximum efficiency zone. Dependent on the wind, waves, and load, the miles per gallon at this pace seem to range between 8-12. Maximum performance has been recorded in calm waters at 19 mph, but gas mileage drops precipitously.

Prop depth of the engine is adjustable with the use of a hydraulic jack plate that can raise the engine straight up 8″ so that the 12″ prop just breaks the surface. If run at idle speed, the prop in this position will power the Gougmaran forward at 4 to 5 mph without cavitating. Thus, the crowning achievement for the Gougmaran is that it can function with good efficiency in waters as shallow as 12″–14″.

The Gougmarans First Cruise

The Gougmarans were launched in 2005 and performed their intended functions well for the first two seasons; several modifications and tweaks were made to both boats. Both have been fitted with centerboards located well forward to improve handling in tight areas. Meade also installed a flip-up rudder in hopes of utilizing a “kite sail” in the future.

The real test of the Gougmaran concept came this spring with a trip down the west coast of Florida from Tarpon Springs to the Florida Everglades. This two-hundred-mile-plus venture south had been in the planning stages for the past year with myself, brother Jan, and sailing canoe guru, Hugh Horton. The basic plan was to take the inland waterway down through the Marco River to the 10,000 Island regions of the Everglades. We would then cruise the Everglades with both Meade’s Gougmaran and the sailing canoes. Finally, we would return home going outside, along the Gulf of Mexico shoreline.

This trip would challenge the flexibility concept of turning a day boat into a live-aboard cruiser that could also take along 3 fully rigged sailing canoes together with enough supplies, gear, and fuel for an extended trip. Altogether, this collection added about 1,300 lb to the normal day boat weight. With crew, this pushed our 2,000 lb maximum payload capability.

The trip began on March 25, 2007, with a launching at Marino’s Marina at our home port of Ozona, Florida, on St. Joseph’s Sound. The first day’s run on the inland passage to Sarasota was uneventful with smooth waters and moderate beam winds. After a pleasant overnight stay at the Sarasota Sailing Squadron, courtesy of our friend and noted local sailor, Charlie Ball, we motored south to our first gas stop. We were delighted when we topped off the tank with just 7 gallons. Up to that point, we had motored about 6 hours and come about 70 miles—ten miles per gallon at a little over a gallon an hour burn. We were overjoyed, but this good news was not going to last. By early afternoon, a building southeast wind began gusting up into the high 20s right on our nose. We reduced our speed, but our tent was acting like a big sail. It seemed to be taking a terrible beating, but it was holding up. We had discussed this potential problem with Rob Kolb, our tent builder, and he said not to worry because most of the covers and side curtains he makes are for boats that go way faster than ours. Over the next three days, as the wind continued to blow hard right on the nose, we gained confidence in our tent structure and finished the trip with our tent intact after an unusually windy 8-day voyage.

Headwinds also impacted our gas mileage. The burn rate increased to 1.5 gallons per hour with speeds down to 10–11 miles per hour. This equated to a drop to 7 miles per gallon, which was understandable but disappointing.

However, our return trip outside in the Gulf balanced this out. With a following wind and waves, we were able to make a return passage of 145 miles in slightly less than 10 hours with a burn of 14 gallons. This put us back in the 10 mpg category, which could have been better had we slowed down to wave speed. At 15 mph, we were continually powering up the backside of waves that were going much slower.

Over the entire trip, we traveled about 490 miles, using 61 gallons of gas in 47 hours of motoring. Thus, we averaged a little over 8 mpg in less than ideal conditions with strong winds over most of the 8-day trip. In more ideal conditions, we think an average closer to 10 mpg is possible. We also want to experiment with different pitch props for any refinements in applying power that could help.

Overall, this trip proved that the biggest success of the Gougmaran was simply its shallow water prowess. At one point, we went hard aground on a gravel bar that was not visible because of muddy water. We all stepped off into the water not much over our ankles and were able to shove the Gougmaran off the bar and into deeper water with relative ease. We were drawing about 10″ of water in the loaded condition. With the jack stand up to max, the 12″ prop just broke the surface, allowing us to go just about anywhere we wanted to with reasonable confidence. We did carry an extra prop and 2 hp Nissan™outboard as a backup.

As we got down into the heart of the Everglade National Park and explored the interior passages, we came out into the Gulf to Turtle Key where we found a protected anchorage with a nice beach to serve as an ideal site to launch the canoes and hang out for a few days. At night, we would strategically anchor the Gougmaran upwind of the island to avoid mosquitoes and no-see-ums. We successfully avoided these pests with our floating movable campsite approach for the entire trip. This is no small victory since this scourge is the only downside to an otherwise unspoiled wilderness where one can wander for days in total peace.

The tent approach worked very well with Hugh and Meade sleeping in the main tent and Jan in his portable tent/cot that was lashed to the front deck and then easily dismantled and stored each morning. All cooking and food handling took place in the tent area.

Overall Jan and I are pleased with the performance and versatility of the Gougmaran on this first cruise. The learning curve was steep, and some changes in the Gougmaran will be made before the next voyage. But they are all minor. The basic architecture of the boat for its intended purpose seems at this point to be right on. Keeping the concept flexible for a multitude of uses with pieces and parts that can be added or deleted is still paramount. The next goal is to outfit the Gougmaran so that it can become a first-rate fishing platform that can support 4 to 6 anglers in a variety of fishing venues. This will also be a new challenge as neither of us has had much time to fish these past 40 years, but we are eager to engage in this new activity that we can enjoy well into our senior years with friends and family.

There has been a lot of interest in the Gougmaran concept with some outright offers to buy our boats. Jan and I are both too old to get back in the boat business, but we are happy to keep experimenting with the concept and sharing our knowledge with others who are interested. At this point, the Newick hulls can be special ordered from Dick Pereli of Still Water Design for those who would like to build their own boat. As this concept matures, we suspect that some semi-custom builders will respond to whatever demand develops.

For more information about the Newick hulls, contact Dick Pereli at Stillwater Design.