A Rendezvous with History

By Bruce Niederer — GBI Technical Advisor

In my article Profile of an American Craftsman the photos of the Les Staudacher jet-powered boat at Marine Services Unlimited provide a photographic history of the first and last run of the Tempo Alcoa. What follows are the details of that historic event.

In 1957 Guy Lombardo and the Royal Canadians were in high demand. The band leader and his music were well known throughout the U.S. and Canada. Lombardo was also a successful and well-known driver of Gold Cup hydroplane speedboats. Prior to WWII, Lombardo had a distinguished 225 cubic inch class career and moved up to the Gold Cup circuit after the war when he bought the proven Champion My Sin from Zalmon Simmons in 1948. Simmons had won the 1939 and 1941 Gold Cup races driving My Sin. Lombardo repowered the boat with a 1,300 hp Allison V-1710 aircraft engine and renamed the boat Tempo VI. Lombardo is credited with as many as 15 Unlimited and Gold Cup victories between 1946 and 1953, but 13 of those victories were in multiclass free for all races that are not recognized in modern historical records. His two big wins were the Gold Cup in 1946 and the 1948 Ford Memorial race–both in Tempo VI and both in Detroit.

In Miami in 1946, Lombardo set a new Gold Cup class record in Tempo VI for a one-mile run with a speed of 113.031 mph becoming only the second Gold Cup driver in history to break 100 mph barrier. He failed to achieve his ultimate goal of besting the Unlimited Class speed record held by the renowned Gar Wood of 124.915 mph set in 1932 in Algonac, Michigan driving his four-engine Miss America X. (Fun Fact: Algonac is the original site of the Chris Craft production facilities.)

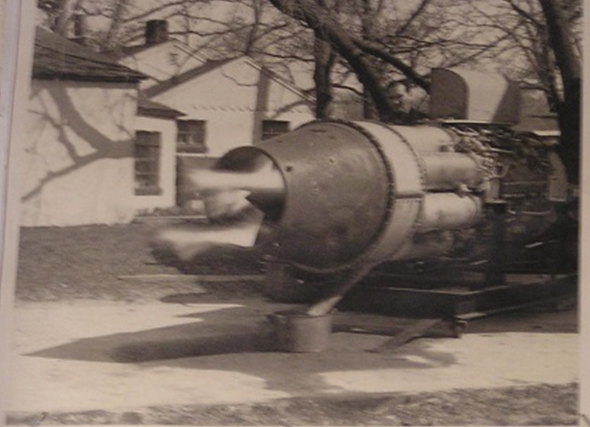

Around early 1955, Lombardo announced he was getting back into racing in a boat being prepared for him by Les Staudacher in Kawkawlin, Michigan — a 30-foot Gold Cup racer with a 1510 Allison aircraft engine Lombardo named Tempo VII. This cemented a relationship between kindred spirits, adventurers obsessed with being the fastest boat ever, evidenced by the fact that Lombardo and Staudacher with the Aluminum Company of America (ALCOA) had already teamed up to work on a jet-powered speedboat with no props. Their goal was to bring the world speed record back to the US currently held by Brit Donald Campbell who piloted his jet boat on a 248 mph run to take the record.

It took Staudacher two and a half months to build the boat, which he designed himself. Lombardo said it looked like a “pickle fork” with the two tines (pontoons) jutting in front of the driver’s seat. Staudacher had to overcome a number of design problems to make this work. There was no deck or foredeck in front of the driver like on traditional hydroplanes.

Hydroplanes operate with about 3 degrees of lift allowing the pontoons to “float” above the water with little but the prop in the water. This would not work with a jet engine because the excessive thrust would cause the hull to take off and fly, flip backwards, and somersault. He took a model of the boat with the engine attached to North American Aviation to test in their company wind tunnel to learn at what speed the boat would fly. Testing showed the boat would be stable up to 460 mph, but the mechanical properties of the structure would not withstand that speed. Still, they were all confident they could reach 300 mph safely.

The first manned test runs of Tempo ALCOA took place in early June 1960 on Pyramid Lake in Nevada. Staudacher made two or three easy runs up to about 180 mph on dead calm water and everyone was very pleased. They were ready to call it a day when a photographer from Popular Mechanics asked if he could get some photos of the boat underway. Les fired up the engine again and made another run for the camera closer to shore, but a breeze had come up causing ripples on the water which doubled the stopping distance of the boat. Staudacher noticed a small peninsula jutting in front of them and too late to stop, hit it at 150 mph, causing the boat to flip over in the air and land right side up in the water. A frantic Lombardo raced down the jetty and fell, tumbling down the riprap, ending up bruised and broken. Staudacher emerged from the water without a scratch on him and drove Lombardo to the hospital in Reno.

The boat and accident received national press attention. Staudacher brought the boat back to his Kawkawlin shop to begin repairs. The rebuild took months, but by spring of 1961, they were ready to try again—this time in Saginaw Bay near Staudacher’s boatyard. But Lombardo was too nervous to let either of them climb into the cockpit, so they spent $2,500.00 on a custom remote control unit built by North American Aviation. They simply couldn’t look inside the sponsons. Had they found all the damage?

They installed the remote controls and Staudacher piloted the boat into the Bay and started “slow” at 100 mph to see how it would handle. Having no problems, Les came ashore, engaged the auto-pilot, set the throttle at half speed, and ran it up to 200 mph. All went well so they pushed it to three-quarter throttle and hit 250 mph. Everything was looking good and they were ready to bring it in when suddenly a sponson came off and the boat veered right and went down with a huge splash while the engine continued straight ahead for a half mile before it sank and disappeared. It turns out the sponson had a defect from the first accident and at 250 mph it broke. That was the end of Tempo ALCOA and the dream of going 300 mph in a jet boat.