By Tom Pawlak — GBI Technical Advisor

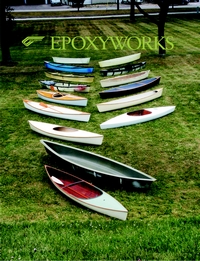

Above: The latest generation of employees and their Gougeon 12.3 canoes.Building a Gougeon 12.3 has become a rite of passage for new employees.

The Gougeon 12.3 canoe represents several decades of experimentation by employees of Gougeon Brothers, Inc. Dozens have been built but no two are exactly alike. The evolution of the Gougeon 12.3 parallels our love of boating, passion for innovation and desire to build better boats—all of which contribute to the products we produce today.

The First Gougeon 12.3 Canoe

It started 35 years ago with a personal project of Jim Gardiner, who was an employee of Gougeon Brothers at the time. He wanted to build the lightest solo canoe possible

Jim planked his lapstrake Gougeon 12.3 canoe with 1/8″ thick western red cedar veneer. The planks were lap-glued together and sealed with WEST SYSTEM Epoxy. He made the ribs with unidirectional carbon fiber tows. This 12′ canoe weighed just 10 lb and drew lots of attention at the Small Craft Workshop in Mystic Seaport in the mid-1970s. It turned out to be a bit fragile for everyday use, but inspired another employee, Robert Monroe, to design a more robust version. Using wood and WEST SYSTEM® Epoxy. He based its lines on the popular Wee Lassie canoe designed by J. Henry Rushton back in the late 1800s.

Robert wanted his canoe stronger. To accomplish this he chose to cold mold his hull using vacuum bagging. He incorporated three layers of diagonally laid 1/16″-thick western red cedar veneer. Robert modified the original Wee Lassie design by increasing the volume at the ends of the canoe. This was around the time Gougeon Brothers experimented to improve the overall performance of sailboats by increasing the prismatic coefficient or curve of areas at the bow (both hot topics in the Gougeon break room during that time). Robert incorporated this feature into his Gougeon 12/3 canoe.

To vacuum bag a cold-molded hull, he would need a mold to form the veneer against. He built his male mold out of strip-planked pine and WEST SYSTEM Epoxy and sealed it with coats of epoxy so it would maintain vacuum without leaking. His hull was designed to be symmetrical; both ends of the canoe had the same shape. This allowed him to build the hull in halves off of the same half mold. He built his mold a bit long and a bit wide to allow room for stapling veneers in place around the perimeter before covering the laminate with the vacuum bag. That way, after the hull half was removed from the mold he could trim away the stapled wood perimeter. He fit and glued together the molded halves to form the hull. Robert’s finished canoe with a deck weighed about 25 lb.

About 24 years ago I wanted to build a small canoe for my children, who were 8 and 10 years old. Robert offered me the use of his symmetrical half mold. He said I needed to laminate two halves off of it and glue them together to create a hull or if I wanted to make more hulls in the future, I should use the half mold as a plug to make two female molds. That way I could glue them together and create a one-piece female mold. With a full mold, hulls would be easier to build and result in a smooth exterior, eliminating the need to make two halves and the work of glassing the seams and fairing. I was familiar with building molds so I took his suggestion.

Because Robert’s mold was made for vacuum bagging diagonally laid veneer, it was ¾” wider than the finished hull half along the centerline. I decided the extra ¾” per side would provide a wider and more stable boat for my kids. This produced a boat that was 1½” wider than Robert’s original hull and about 4″ longer. The result was extra buoyancy for paddling down Michigan’s shallow rivers.

I built two canoes from this mold. The first was a fiberglass/Douglas fir veneer hybrid I vacuum bagged. I decked the ends and left the center open. About 15″ from each end I added watertight bulkheads made of epoxy coated 4mm plywood. This provided enough buoyancy to keep the gunnels flush with the water even if the boat has a person aboard and is swamped.

The second boat employed the same fiberglass/Douglas fir veneer lay-up. I shortened the sides of the hull near the ends to produce a sheer that would be parallel to the waterline. This flat sheer line, decked over, gave the boat more of a kayak appearance. The deck ran the full length of the boat, making it much drier in rough water. The lower sheer near the ends allows it to handle wind better than the first canoe I built out of this mold. The decks were made in the hull mold by utilizing the bottom of the mold near the ends.

The Little Mold Becomes and R&D Tool

In the years that followed, we used the little mold to prove concepts for producing the Gougeon 32 (G32), the first production-built epoxy boat that had a polyester gelcoat applied in-mold. Long before the first G32 we used this mold to make experimental canoes. These incorporated polyester gelcoat and conversion coatings laminated over with epoxy, biaxial fiberglass fabric, end-grain balsa, and foam cores. All of these canoes were built using vacuum bagging techniques.

Before building the molds to produce the G32s, we experimented with different tooling gelcoats, fiberglass lay-ups and cores. Then we produced a master plug off of the little canoe mold. We used experimental resins and hardeners with different pigments and different thickeners in several locations along the length of the mold so we could see how well each of them buffed back after sanding. We also experimented with different epoxy formulations to see which provided the most stable surface with the least amount of print through when applying fiberglass.

Once the master plug was released from the canoe mold, sanded, and polished to perfection, we made a high-quality production mold off of it with the resin/hardener and fiberglass combinations that produced the best results in the master plug. This new mold came off the master plug looking flawless. Based on what we learned about making the canoe tooling, we were confident we had the answers needed to produce the G32 tooling.

A New Mold Plays an Ongoing Role in R&D

The new canoe mold came in very handy before and during the production of the G32. We used it to learn how to make molded parts without print-through (that annoying fabric pattern you sometimes see in glossy gelcoats on fiberglass boats). Exposing the laminate to higher temperatures for several hours—after the epoxy had cured to a hard gel, and with the part still in the mold and under vacuum—eliminated print through. We used it to experiment with different cores. We learned that when vacuum bagging, care must be taken to not get too much resin in the fiberglass applied to the gelcoat, and that perforating, slicing, or scoring a grid in the core eliminates air bubbles between the gelcoat, fiberglass, and core.

The side benefit of these experiments was all the Gougeon 12.3 canoes that became available inexpensively to our employees.

Robert later used the mold to build a biodegradable canoe out of epoxy, balsa, and hemp fabric. He learned that the hemp fabric was difficult to saturate with epoxy, but it did produce a light, efficient canoe. If you were to leave this canoe in the sun and weather without any paint or exterior varnish protection, UV light degradation would allow it to disappear into the environment for over a decade or two. Stored out of the sun and used several times a year the boat will remain intact for a lifetime.

More recently we’ve used the canoe mold to experiment with infusion resins. Five of our employees made beautiful fiberglass hulls reinforced with unidirectional carbon fiber ribs and keels. The boats are a bit eerie to paddle in because it’s like paddling in a glass-bottom boat except the whole bottom and sides are transparent.

Over the past 24 years, employees have produced dozens of canoes from the molds. Some are made of sophisticated fabrics and foam cores, others are fiberglass and balsa cored that were vacuum bagged to produce strong and light craft. Others were made with a couple of layers of biaxial fiberglass by hand lay-up without vacuum bagging. Some boats received small decks while others were completely decked over with an opening just big enough for an occupant to slip into.

The canoe did not have a name until recently when an employee looking to build one inquired about where the mold came from. After hearing the story, he named the canoe the Gougeon 12.3.

Editor’s note: For more on this mold, read Turning a Gougeon 12.3 canoe into a Gougeon 12.3 kayak.