by Captain James R. Watson

Lady B is a sailing sharpie I launched on August 20, 2009. On one of the first sails, I asked Jan Gougeon to come along with me to see what he thought of her. That sail brought back many memorable sailing moments that Jan and I have shared over our lifetimes.

Jan Gougeon grew up on Donahue Beach and I on nearby Aplin Beach. The two beaches were separated by Wenona Beach, a magnificent amusement park built at the turn of the century. We were in the same kindergarten class. It wasn’t long before we were both in boats we’d built: Jan in his 13′ Dart and me in my 8′ pram, the Pal. Back in those days, we built using bedding compound and lots of screws. We carried coffee cans to bail our leaky boats.

Around 1955, my two means of transportation were a bicycle and my boat. Similarly, Jan had a boat but he also had a car—a buggy he’d assembled of bicycle wheels, a wooden frame joined with nails, bolts, and brazed metal parts. It was powered by a gasoline-fueled washing machine motor. The buggy’s body was painted black and there was even a fringe on top. I could hear the putt putt putt of Jan coming from a long way off. I’d jump on my bicycle and we would head for our boats.

Jack Taylor’s

A favorite excursion in our boats was up the Saginaw River to Jack Taylor’s. He was a bohemian, an engineer, a voyager and a creator of all sorts of things. Taylor lived in an A-frame accessible only by water, amid a bunch of closely built, ramshackle, abandoned fishing shacks all adjoined with rickety docks. These were connected to the Coast Guard Station which was located within the Saginaw River Rear Range Light. On a barge next to his A-frame Taylor was building Teal, a strip planked 22′ yawl edge-nailed with ring-shanked boat nails. Gaps existed between the planks but when the craft was sheathed with fiberglass and polyester resin, the excess bonded the strips together. We were just learning about fiberglass and polyester resin; we had only heard about epoxy.

Taylor’s was a wonderful place where we could explore the labyrinth of shacks and pester the Coast Guard personnel until they would let us climb the Saginaw River Rear Range Light tower (which was similar to a lighthouse). The whole experience inspired us both enormously. Taylor’s enthusiasm for building was contagious. We would work for him in exchange for old sails or hardware. A bronze gooseneck, for example, was a priceless piece of “boat jewelry” we coveted, for our simple craft were fitted with plain, homemade fittings. We’d leave Taylor’s full of ideas, solutions to boat-related problems, and a zest for boats, design, building, and adventure that would last throughout our lives. We never did earn enough credit to possess the gooseneck.

Presto

Around 1960, Jan’s grandmother Ollie took us in her huge Buick Roadmaster about 30 miles from home to AuGres. There we boarded an 18′ Corsair (a French designed and built class that exists today) that we were allowed to sail for the summer in exchange for repair and maintenance. We used epoxy for some of the repairs and learned a lot of repair strategies. She was a V-bottom, plywood boat. She had a cabin with bunks, and a keel/centerboard configuration and for us was qualified as an offshore cruiser.

It was our first experience with Dacron sails: all our boat’s sails were made of cotton, and most of them we’d sewn on our mothers’ sewing machines. We named the Corsair Presto and sailed her all that summer, including a local long-distance race to Gravely Shoals and back (about 60 miles). After we’d rounded the Gravelly Shoals Lighthouse and were headed home, the wind freshened from the north. We were surfing fast so to lighten the load we started jettisoning stuff. We threw all of our hard-boiled eggs into the air and as they splashed behind, we were convinced that we would pass all of the competing boats, which were much larger than Presto. Unfortunately, the wind then went light and south. We hand to beat all the way home to finish late in the night, far behind the others, and quite hungry.

Wee Three

Jan’s first trimaran, Wee Three, was 18′ long and one of his own design. He now lived in town and built the boat outside in his backyard. She was made of 3mm thick plywood over light spruce stringers. All components were joined with epoxy that was poured and mixed from glass fruit jars; there were no calibrated pumps in those times. We did not coat surfaces with epoxy then, but the joints were tight: no more leaks. I was an altar boy then and recall the early morning, before mass, that we launched her.

Wee Three was transported on the top of Grandma Ollie’s Buick (Jan was now old enough to drive a real car) when one of the outriggers fell off on the way to the yacht club. Following in my dad’s car, I picked up the outrigger and put it though the window into the back seat. We took turns sailing Wee Three with her DN iceboat rig. The non-skid surface was so aggressive we both had bloody knees and feet after sailing her. I had to go serve mass later and my socks stuck to my feet as the blood dried. But all through the mass all I could think about was what a thrill that boat was to sail.

Riddle

The next year I completed my William F. Crosby-designed Crosby 16, Riddle. I built her outside of plywood, oak, spruce and epoxy. Jan was there to help me install the centerboard case, a huge fitting and gluing job for us. As the night wore on we kept breaking light bulbs and eventually stole all of the bulbs from my mom’s house. The oak-to-oak joints never gave any problems. Jan was with me on the first sail of Riddle. Many times Riddle andWee Three would gallop along side-by-side over the waters of the Saginaw Bay.

Cruising in an OK Dinghy

By the mid-sixties the United States, draft board had contacted us both and together we boarded Glider, my 13′ Knud Olsen-designed OK Dinghy I built in 1964. This was a high-performance planing dinghy with a free-standing rig. Jan and I went on a three-day voyage in Canada’s North Channel to contemplate our destiny. We had two dive masks but only one set of fins, thus we each wore one when diving in the crystal clear water. All we had was a few cans of beans, a loaf of bread, and some peanut butter. We still talk about that cruise. Eventually, we both were drafted and served in Vietnam: Jan with the Army and I with the Marine Corps.

The projects were dismal failures but we still laugh that “there was nothing magic about Magic and Firecracker was a dud.”

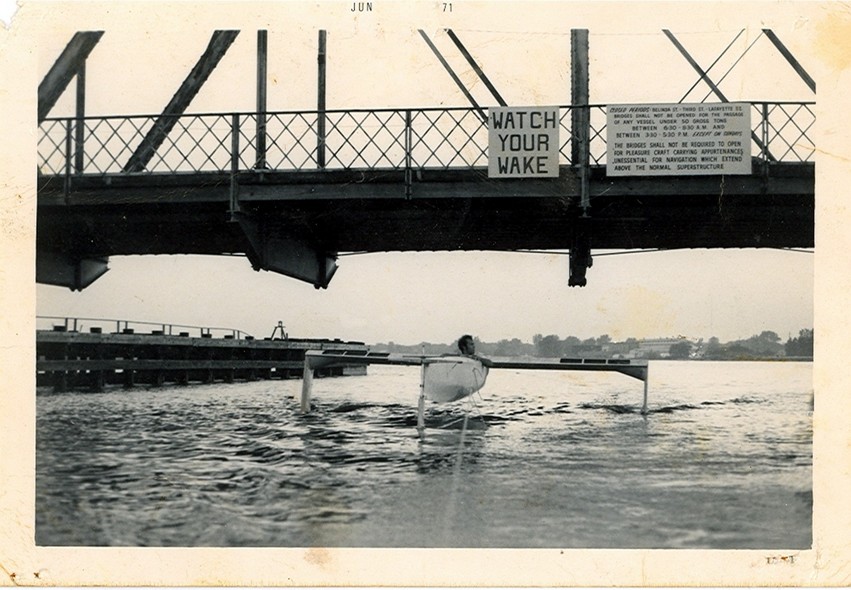

Hydrofoils

Some of our more daring failures were our ventures with hydrofoils. Jan’s was the Firecracker and mine the Magic. By now we had learned the value of coating the interior and exterior of a structure with epoxy. Previously, we used epoxy only as a glue. But formulation experimentation allowed the epoxy to be spread in a thin film so the structure remained lightweight yet protected from the harmful effects of moisture. The hydrofoils structure—beams, hulls, and foils— were made of thin plywood. Talk about complicated to assemble and launch.

At first, we did tow tests with a powerboat and they flew—came out of the water. Once sailing they flew but were terribly slow due to excessive wetted area and drag from the large, fat foils. The projects were dismal failures but we still laugh that “there was nothing magic about Magic and Firecracker was a dud.”

Still, we learned much, especially about fastener bonding and foil shapes. We discovered the zit staple, a fine wire staple that can be left in the structure. We used these to “clamp” thin plywood. We discovered the value of bonded dowels and threaded rods as tension elements. We also began bonding wire and rope into the structure with great results—strong, clean and simple attachment.

Iceboats

We sailed iceboats for years. In 1975 Jan took first place and I took second in the DN Iceboat Gold Cup World Championships. We beat the fierce sailing Russians, Poles, Dutch and Swiss. That was great fun and done with sails that we made ourselves.

The DN iceboat is a plywood/spruce structure that is highly loaded and really served as a test platform for what could be done with epoxy. Jan’s boat was beautifully varnished like a piece of fine furniture. Helping transport race committee equipment after the race, he had put among other things a can of bright orange spray paint in his cockpit. He accidentally punched a hole in the can with his foot spike, and, not realizing this, sailed in. What a mess the paint made of the nice woodwork.

Jan and brother Meade Gougeon went on to win many DN Championships. Meanwhile, I switched to downhill skiing.

Splinter

Then there was the time we rendezvoused in North Channel. Jan was on his honeymoon aboard his new boat Splinter, so I show up out of nowhere in a 10′ pram I borrowed. We snorkeled in the same waters as we did from the OK Dinghy back before the war.

Splinter was a 25′ trimaran, wider than it was long and it utilized water ballast. This was Jan’s first attempt at a self-righting multihull. Jan was about the only one in the world to pursue this concept. Other self-righting multihulls of Jan’s design include the 35′ trimaran Ollie and the production G32 catamaran. In fact, Jan and I sailed the prototype G32 in the Gravely Shoals race just as we did decades before in Presto, only this time we didn’t throw our food away.

Project X

Jan’s newest boat is another self-righting design. For now, it’s called Project X. (I know what the real name is gonna be, but I ain’t telling.) I’m hoping I’ll get a ride on her when she’s launched this spring. Jan says, “Its probably the most complicated structure I’ve ever built.”

Lady B

Lady B is a Howard I. Chapelle-designed sharpie he called Dandy, based on Commodore Monroe’s Egret. I first saw this design when Boats magazine featured a series of articles titled The American Sharpie Yacht 1958. I kept those magazine articles and eventually built the boat with WEST SYSTEM® Epoxy. Dandy is a modification of Monroe’s design, so I thought it fair enough to make few modifications myself. Composite chines work very well to round the corner. I also installed a daggerboard instead of a centerboard thereby saving a lot of room below.

Accommodations below consist of two comfortable seats, toilet (with holding tank) and huge bunks, all with sitting headroom. I was going to have a modern rudder configuration with a turntable cassette and dagger-type rudder but that didn’t work out. We were concerned about the shallow ‘sharpie’ rudder as designed, but were amazed at how well that works. I think this is due in part to careful shaping of the foil section and end plating to hull bottom. The rig is self-tending when tacking and this sprit configuration is self-vanging. I am still tweaking the split sprit rig configuration, which I had no previous experience with. It’s working fine; fundamentally they’re simply two free-standing masts not unlike the OK dinghy.

Lady B is more stable that you’d think and tacks within 90 degrees. The general rule regarding sharpies is to keep the top hamper—everything above the deck—as low as possible, so the higher I got in the structure the more effort I spent in saving weight. The cabin roof is thin plywood with a balsa core and carbon skins. The carbon fiber spars are by Composite Engineering/Ted Vandouzen in Concord, Massachusetts and are incredibly light. They can be raised via removable tabernacles (no outside assistance required) that double as rests when the boat is trailered or stored. The masts bend in puffs, thereby de-powering the rig.

Sails, cut to match the bend of the spars, are by David Beirig of Erie, Pennsylvania. David Carnell of Wilmington, North Carolina, gave me the offsets and lines as the magazine article had only construction drawings. The craft nicely fits the definition of a trailerable, easily handled, smart sailing, thin water cruiser. It took about 1,000 hours to build. I envision Lady B and, ahem, Project X sailing side by side next year, but not for long as I predict the latter to whiz by my little sharpie in no time.