By Grace Ombry

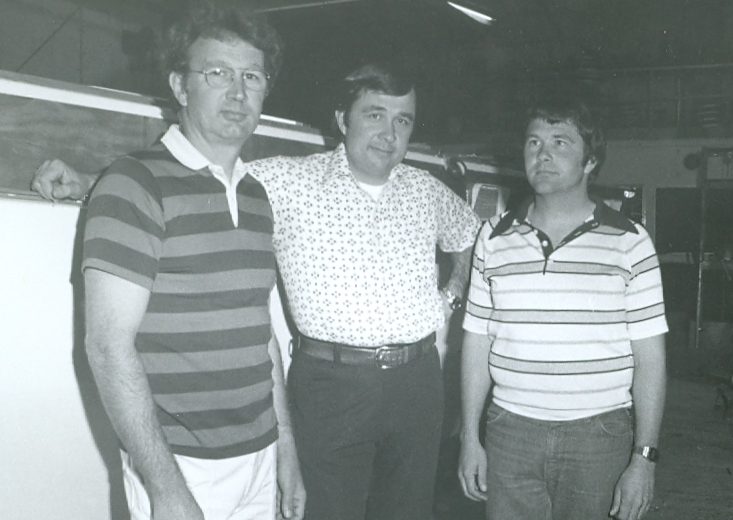

On June 20, 1979, while sailing in a qualifying race for the OSTAR (Original Single-Handed Transatlantic Race), Jan Gougeon’s self-designed and built 31′ trimaran FLICKA was capsized by heavy seas in the North Atlantic. Jan survived on the overturned plywood/epoxy multihull for four days before he was rescued by a passing freighter. The following is the second half of a transcript of a phone call between Jan, his brothers Meade and Joel, as well as fellow multihull designer/sailor Mike Zuteck. Their discussion takes place on June 26, 1979, just hours after the freighter that rescued Jan delivered him to dry land. Part 1 of this conversation can be found here.

FLICKA was never recovered.

We’ve divided their lengthy discussion into two parts. At the end of Part 1, Jan described the feeling of leaving FLICKA behind after his rescue. In this installment, he goes on to discuss the failure of his EPIRB unit, what he learned from surviving FLICKA’s capsize, and his conviction that all multihulls should be self-rescuing.

Meade Gougeon: Weren’t the outriggers holding it up pretty good though?

Jan Gougeon: Oh, everything was perfect, yeah. No, the boat to this second-if someone would go out there and get it-all they’d have to do is patch two holes and the boat is perfect, outside of I removed a couple of pieces of the furniture inside to make things. But the boat is structurally, absolutely flawlessly, beautiful. As a matter of fact, I took the time yesterday—while I was stringing up this thing—to look at the A-frames. I was concerned about the A-frames being loaded that way. I was thinking of unbolting one outrigger and trying to right it. But I didn’t want to take the chance of losing what I had as a good survival platform. I mean it was perfect. I had it so perfect for surviving in that I figured if I had to stay there for a month, I was going to be able to handle it.

If I ever tried to start unbolting stuff, the chances of something hurting me… As soon as I ever got an arm broken or something, I’d die. You know I knew that. Or even a bad cut or something. I couldn’t take many chances. Even though the water was warm, when I worked on the boat I put on my wet suit and boots and anything I could to protect myself so if I fell I wouldn’t cut myself.

Meade: Anyway, [boat designer] Damian McLaughlin called and said that the waves in the Gulfstream were running 35 feet.

Joel Gougeon: He said that every twentieth wave was running 35 feet.

Jan: Well I’d say, I never went across the Gulfstream then, that it was good I didn’t sail there. I would say at that point, on a trimaran unattended, the only way that it would survive—and I say any trimaran will survive almost anything if you have a sea anchor to keep the nose into the waves—I don’t think anything will get it. That’s my feeling right now.

Meade: How about going downwind with it?

Jan: Downwind would be no sweat. But I think that going head-to-wind, the problem with [going] downwind is you need a person to steer it.

If you had a head-to-wind, the bows are nice and fine and the sea will kind of crash over it, but it would never tip over.

Joel: How high were [the seas] running when it flipped over?

Jan: Oh, I’d say the [wave] that tipped me over was probably 14 feet. I didn’t see it but it was bigger than the rest. I didn’t want to get into the Gulfstream because I knew it would just, you know. It was death. It would be death.

Meade: But you had the mast up with some sail area on it, though? You had a double-reef main?

Jan: Double reef main, the mast feathered in the wind. If only I had stayed up and sailed it. I ain’t kidding you, the boat with that rig will sail to weather in 50 knots of wind with ease. No problems at all if you’re steering it. As long as you’re steering it, it’s not a problem. As soon as you go to bed though, the boat can’t take care of itself. It needs a sea anchor.

Boy, the first two days I had such a fabulous sail though. So fabulous you wouldn’t believe it. It’s something like you dream about. Like cross country skiing only it’s always downhill. Fantastic, man. It’s going off the wind and the genny, about half the jib rolled out and one reef in the main. The boat would get on these waves and you’d surf for maybe four or five minutes, going like hell, just beautiful control. And it would hit the next sea and the shape of the outriggers and everything worked so beautiful. There was never even any tendency of nose-diving, never any want to broach, nothing. Unbelievably controlled.

Meade: Did you have the boards down?

Jan: The boards were down. When I was hove-to I had the leeward board all the way down and the windward board up to keep the nose into the wind. The boards up and the boat sitting to beam would never work. The boat never even started to want to go sideways, it just went straight up and flipped over. It was like someone stuck a stick under me and pushed up in the middle of the boat. It’s absolutely treachery to lay beam-to. Not the way to do it. And the weight of the boat doesn’t matter. It doesn’t matter if it weighs 4,000 pounds at that point. See, what happened when the boat was upside down with the cabin full of water it, was more like a catamaran with the two hulls far apart. All of a sudden that gets real stable in the waves. I think of it like a proa*, the main hull is actually a nuisance when you’re beam-to, it shouldn’t be there, it’s something for the waves to hit.

I haven’t got money problems at all. There’s no hassle that way. I even saved my American Express card, I mean, believe that? It’s still in my wallet. They make them out of pretty good stuff. Whatever it is, it held up pretty good.

My ultimate, ultimate point of depression though was standing on the bridge watching my boat disappear behind the ship.

Meade: You had to be pretty happy to be alive though, Jan, didn’t you?

Jan: That’s what I told the captain. I said, “I still have two hands and I can build myself another boat.” A little bit of plywood and some staples and glue and you get another one.

I’ve had so many great gobs of things to contribute to any of these guys going out to sea on what they should do to be ready, though. If they’ll listen to me and believe me, anyone who does all the things that I tell them will always come home again. It’s so simple to come home again if you do these few things. Almost any trimaran can have these particular qualities that my boat had. It’s obvious what the flaw is when the boat is beam-to. The main hull just displaces. It’s 30-feet long and the wave immediately moves the boat because it displaces the entire length of the boat, you know what I mean? So immediately the boat starts going up. Well, when the boat meets the wave head-on, the wave can go right up to the sheer of the boat and it only displaces a small percentage of the weight of the boat because of the shape of the wave.

Nothing happens to you head-on. But [a wave approaching] beam-to will flip you. Every trimaran I can imagine is afflicted by that. The beam is everything right then. The distance between the main hull and the outrigger is the whole key. Because the angle that it finally gets at is less, but the displacement of the outrigger means nothing. The outrigger didn’t even-as a matter of fact, the boat didn’t-it took a side slam after it got up in the air. It dropped, and when it tipped over I thought that the outrigger had actually busted underneath. That it had busted the ends of the beams off is what I had the feeling had happened. But when it was upside-down it seemed to be floating pretty level and so the seas weren’t hitting the main hull. I couldn’t see out at that point, so when I cut [my way] out, I of course cut on the side of the main hull. I looked and everything was still there. All the boards and everything were still operational and everything was like brand new.

Meade: So you didn’t lose any of the stuff out of the inside of the boat?

Jan: Well, I lost all the canned foods. They were gone instantly. Anything that sank got sucked out of the main hatch as fast as it could. But all of the rest of the food… I had a lot of dried food and packaged food that was stored in these little bins and stuff. Another key thing is you’ve got to have some covers on the bins so the stuff doesn’t fall out. But I grabbed stuff as fast as I could. I mean, the fabulous cuisine of the transoceanic I could see glowing underneath the saltwater. I immediately grabbed the [fresh] water-first thing-and then the food was next and tools. As fast as you can grab stuff, you grab it. I’ll tell you, the really scary thing would be tipping over in the dark.

Joel: What time was it when you flipped over?

Jan: It was about four o’clock, I think.

Joel: Oh, in the afternoon.

Jan: Yeah. My [wrist]watch worked through the whole thing. But, anyway, I looked at my watch. As a matter of fact, I kept a log of the whole thing. But [when] I left I didn’t grab it all. I even had the log right up to the point I tipped over. It went down. I was working out the sight and I had paperwork of the sight. I saved that, but left it all on the boat when I ran out of there. Some of the—

Meade: You actually summoned the freighter? The guy saw you though? You didn’t call him on the radio you just…

Jan: No. I didn’t have a radio.

Meade: He just saw you.

Jan: He saw me, yeah. I stood on the bottom and I had on a yellow-you know what you call it-and everything.

Joel: What about that Nicro beeper or whatever the hell it was?

Jan: Oh, let me tell you about the Nicro beeper. I mean, [it was only] worth a few minutes.

Meade: The EPIRB [Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacon]?

Jan: Yeah, the EPIRB, right? OK, the first night I flip over I’m upside down. I figure, tonight I’ll turn on the EPIRB and tomorrow they’ll come and pick me up, right? So I turn on the EPIRB and I hang my [man overboard] strobe light outside. I put the EPIRB out there and the red lights on. Come morning, I notice that the little red light is out on the EPIRB. I bring it back into the cabin and the thing is real warm. So I tear it apart. Inside is a big cloud of smoke. One of the wires has gotten pinched and the thing was shorting out. I take it all apart and carefully scrape off all the stuff. I get the EPIRB back together and it lights up again. I don’t know whether it is broadcasting or not anymore. The thing failed. It’s supposed to work for eight days. I don’t think it ever-probably ever in its life-broadcasted a signal. So that was just all false security.

Mike Zuteck: That’s too bad.

Jan: The VHF radio thing, you can hear them talking and stuff so you know it’s working. You know you can talk to them. And if they don’t answer you, or if they answer you and it’s garbled, at least someone is hearing you.

Joel: Yeah, having a good radio onboard would be the way to go.

Jan: You can’t have a regular radio because that gets underwater and it depends on the ship’s battery. You’ve got to have a handheld VHF. You know, the little handheld job that I was looking at, the six-channel one. That’s the only way because the regular radio is operating on the ship’s battery and those are gone. I had big piles of flashlight batteries, so in the back cabin I had a workshop made and in one of the little areas was a work table. I tore the EPIRB apart and cleaned out all the burned crud in between the little jobbers, figuring I could maybe save it. I tore the EPIRB’s battery pack apart to count how many batteries were in it to figure out the voltage, see. When I figured out how many volts it was, I hooked all these flashlight batteries and stuff together to get the right voltage. Among great sparks and smoke, nothing ever did EPIRB again. So I gave up that idea and I figured maybe I could start cutting parts of the boat off and light them [on fire] and let them drift.

Joel: Well, when you were in the back cabin it was fairly dry there?

Jan: Yeah, I was high and dry. Well, there was some surge that would splash in there once in a while, so I took one of the tables and I cut it to fit in there with a towel. I measured about 38 times and I made this line. It was one of those fits where you have only one shot at it because it is going to take you four hours with a hacksaw to cut it. I cut it, put the towel around it, drove it in there with the winch handle. The forces of God would never have moved it. It will be there until the day someone finds the boat and salvages it. They’ll just have to put up with that piece of wood in there because that’s how tight it’s driven in there. And no more water ever got in the back compartment, outside of the window leaking a little bit. The window would have been a nice strong window. It would have stayed dry forever, fully waterproof. Absolutely fortified there. Absolutely, the answer to survival is the place where it’s dry. You’ve got to stay dry and out of the water. After the first day, the sleeping bag got kind of wet. But during the day when it was kind of calm for a while, I opened up the picture window in my back cabin and dried out the sleeping bag.

I took the other table-half with the little pin sticking out, wrapped line around the pins, then cut holes in the side of the boat with my jackknife. I tied the lines around it. I could tie it down at night real tight. I stuffed all my extra clothes in it so that water wouldn’t leak through the cracks in the cabin. I’ve got a pretty good report written for the Coast Guard that I got a copy of. I’ll bring that home.

Great amounts of stuff learned in the multihull thing. It’s not a dead cause yet. The fact that I survived, the only thing that I won’t do, I mean, the criteria for my next boat is it’s still got to be fast. But it’s got to be self-rescuing. And it’s got to be able to be hauled behind my Honda. That’s the criteria.

Editor’s Note

Jan would go on to design his first self-rescuing 25′ trimaran, SPLINTER, launched in 1980. SPLINTER placed first in the Port Huron to Mackinaw Race in 1981, 1982, and 1983, and also set a record for fastest finish. Built of plywood and WEST SYSTEM® Epoxy, SPLINTER is still racing on the Saginaw Bay 40 years later.

Jan went on to design and build the 35′ trimaran OLLIE; the trailerable GOUGEON 32 catamaran; and the folding, trailerable 40’ catamaran STRINGS. After FLICKA’s capsize, every sailboat Jan designed featured self-righting capabilities. All of Jan’s sailboats continue to compete on the Great Lakes today.

Jan passed away in 2012 and was inducted into The National Sailing Hall of Fame in 2015. We miss him dearly.